Attabotics Is Back — Can Customers Trust the Brand This Time?

Attabotics is returning to the market.

After its 2025 collapse and asset sale, the brand is being relaunched under new ownership and new management — with the official public launch planned at MODEX 2026.

We’ve covered what went wrong the first time: Scott Gravelle’s management style and leadership decisions, multiple warehouse fire incidents (including Nordstrom and Canadian Tire), and a software maturity gap that never reached production-grade reliability. Next, we’ll break down what’s changed, what hasn’t, and what automation buyers should verify.

How Calgary tech darling Attabotics went off the rails

By Jesse Snyder at The Logic

When fire crews in California’s Bay Area were called to a Nordstrom distribution centre in April 2021, one of the first firefighters to reach the scene declared that it was “going to be a weird one.”

The building’s alarms and sprinkler system had gone off, and firefighters had traced the source of the smoke to the centre of the facility, according to radio communications between first responders. The blaze was in check, the firefighter added, but his team was “having access issues” because the smoke was coming from “one big box that goes damn near to the ceiling.” Getting at the fire was no straightforward matter, he said, catching his breath: “We have robots that, uh, move inventory within a closed structure.”

Talking Points

• Attabotics, a prominent Calgary robotics startup that raised more than $200 million, entered bankruptcy protection in July

• The filing delivered a blow to Calgary’s tech sector, where Attabotics was seen as a potential anchor company if it could deliver on its early promise

• Drawing from court documents, financial reports and interviews with sources familiar with the company, The Logic found that persistent technical troubles with its robotic warehouse tech, including at least three fires, hobbled the company before it entered protection

The sprinklers and fire crews eventually doused the flames. But the blaze temporarily shut down the department store’s experimentation with an emerging technology that at the time was stirring excitement in the worlds of logistics and retail. The robotic warehouse system belonged to Attabotics, one of Calgary’s leading tech startups and a Canadian champion in the fast-growing space of supply chain automation.

Attabotics got past the incident, and would later sign deals with other big-name clients. In hindsight, though, the fire was an ill omen. More than setting back its work with an iconic U.S. retailer, the incident was one of many technical issues that were already hobbling the startup and its technology—lapses that, four years later, helped bring about its financial collapse.

In early July, Attabotics entered bankruptcy proceedings, as years of declining revenues and high costs tested its financial viability. The company abruptly laid off 192 employees leaving a written notice on the door of its Calgary office and retaining a small workforce of 11 as it sought to sell its remaining assets.

It was a dramatic turn of fortune. Co-founded in 2016 by CEO Scott Gravelle, Attabotics’ unique robotics technology had helped it secure $200 million in funding from investors, including U.S. industrial giant Honeywell, San Francisco’s Forerunner Ventures and New York-based Comcast Ventures. In addition to Nordstrom, its customer list included established companies like Canadian Tire and U.S. media company Accelerate360.

Based on the swarm movements of ant colonies, the technology uses fleets of small robots to sort, collect and distribute warehouse inventory. Unlike conventional systems that essentially pluck items from warehouse shelves, Attabotics’ robots move along vertical and horizontal tracks housed within a giant, featureless cube. The technology’s three-dimensional orientation lets it store and move goods—anything from pet food to T-shirts—in a more condensed way, saving potential customers costly warehouse space.

That value proposition, and the money it attracted, gave Attabotics an outsized presence on Calgary’s tech scene—one all the more striking when things fell apart. To trace the arc of its rise and fall, The Logic examined court records and financial filings, while interviewing supply chain industry experts and five people familiar with Attabotics’ operations, including four former senior employees. The Logic granted anonymity to its sources because they were not authorized by the company to speak publicly about the events leading to the bankruptcy.

The insiders describe a startup that aggressively pushed its technology to ever-greater limits, even as technical glitches prompted repeated shutdowns, drove up costs and complicated relationships with customers. Three fires—one at Nordstrom, a second at a Canadian Tire distribution centre in Ontario, and a third, much larger fire at the same Canadian Tire warehouse—interfered with the company’s efforts to climb to the top of the highly competitive supply chain and logistics market.

Even though Attabotics continued to attract major pools of investment, Gravelle’s relationships with staff, some customers and at least one investor began to sour, three sources said. Communications with investors became sparse, and the company started to churn through executive staff. Its three other co-founders—Jacques LaPointe, Anthony Woolf and Rob Cowley—all left the firm between October 2018 and July 2020, although none publicly stated his reasons.

Gravelle’s fundraising success had instilled a “too-big-to-fail mentality,” one person said, and as the startup’s financial woes continued, it became embroiled in lawsuits against customers and outgoing staff members alike.

Attabotics did not respond to The Logic’s request for comment for this story. When contacted, Gravelle told The Logic he had received a cease-and-desist notice that prevented him from speaking to media. He did not respond when asked who sent the notice.

While Attabotic’s impending collapse didn’t surprise insiders, the blow it dealt to Calgary’s nascent tech sector was severe. Long associated with its vast oil and gas wealth, the city has sought to diversify its economy toward emerging fields like fintech and clean energy.

Despite making strides in recent years, the size and range of Calgary’s tech community continues to lag that of other Canadian cities, and it has yet to produce its own $1-billion tech champion—the sort of anchor firm that Shopify was to Ottawa, or AbCellera is to Vancouver.

Attabotics counted among a handful of startups that—to outsiders, at least—looked poised to break that barrier. The company raised hundreds of millions in the span of a few years, regularly topping fast-growth lists. In 2019, Time magazine gave Attabotics’ technology a special mention on its annual list of best inventions.

Gravelle seemed keen to feed the excitement, boasting that the firm’s system could ultimately disrupt the entire e-commerce supply chain. In a TED Talk in 2019, he said Attabotics had developed “the world’s first 3D robotics shuttle” that would all but eliminate the need for cardboard boxes and air cargo, reorienting supply chains around smaller distribution hubs that could automatically sort and distribute goods.

Starting around mid-2018, Attabotics enjoyed a growth spurt that launched it from a seed-funded startup to a robotics company with major clients. At the time, the firm had built a testing facility for its robotic system in Calgary and was piloting its technology with Gordon Food Service, a grocery distributor in the city.

That summer, it started working with its first major client in Nordstrom, which three sources told The Logic was also an investor in Attabotics. (PitchBook does not list Nordstrom as a current or past Attabotics investor, but sources said the retailer later sold its stake.) Nordstrom did not respond to The Logic’s questions.

Attabotics needed on-site personnel to rescue the robots. “We hired an army of people just to babysit it.”

Under the deal, Attabotics agreed to install its technology at Nordstrom’s Newark, Calif., distribution centre—the same facility that would catch fire a few years later. It was a sizable leap for Attabotics in both capacity and software requirements. While the Gordon Food installation ran with about six robots, the Nordstrom plans would require around 18, according to one senior source.

Gravelle set an ambitious timeline to scale up capacity at the Newark project—internally coded contract “499”—with initial testing starting around July 2018. He aimed to ramp up to commercial installation by January 2019, a narrow window given that the Attabotics system was repeatedly malfunctioning, lagging far below the industry standard of being operational 99 per cent of the time, according to three sources familiar with the project. “For sure, the system wasn’t ready,” one former senior staff member said.

Among the issues plaguing it: robots occasionally failed to properly latch onto their tracks before descending the shafts, and would crash to the warehouse floor, two people said. In the first two days of testing at the Nordstrom facility, 12 of the 18 robots fell off the tracks or otherwise malfunctioned, said one person with knowledge of the project.

Attabotics needed on-site personnel to do “robot rescue”—essentially, hoisting the units back onto the track system. The additional staffing requirements accelerated the company’s cash burn. “We hired an army of people just to babysit it,” said one source.

The Attabotics system’s reliability would improve as staff tested thousands of new robot iterations. (In 2022, it started incorporating AI into the system.) The Newark system was one of Attabotics’ first prototypes and, given the complexity of the hardware, some defects were to be expected, said one person familiar with the company’s technology. Ideally, the firm could have refined the technology at its Calgary test site, then moved on to commercialization once the hardware and software kinks were ironed out, three sources said.

“I told Scott, ‘I believe your company is going to fail. Frankly, your cash burn rate is an embarrassment.’”

Instead, Attabotics rapidly moved onto bigger and bigger contracts. Despite a rocky start at the Newark facility, Nordstrom ordered more systems. In the space of a year starting early 2019, the retailer installed Attabotics’ tech at its warehouse in Maryland and its Los Angeles “omnicentre” distribution hub. Even with the technical setbacks, one former Attabotics employee said, “we were rolling out project after project after project.”

Described by former colleagues as a “dreamer” and a “passionate” salesman who constantly pushed his vision for Attabotics, Gravelle took an unlikely path to founding a high-profile tech startup. Before launching the company, he worked as an army medic and later ran a longboard manufacturing firm.

Former employees and other sources said Gravelle is a gifted storyteller, capable of convincing would-be investors about his technology’s potential. His pitch even won the attention of legendary investor and SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son, whom Gravelle said he met in Japan in the summer of 2019 to discuss Attabotics’ business and technology, according to one person familiar with the meeting. A short time later, Attabotics agreed to supply its system to Gopuff, a food delivery company backed by SoftBank, according to the details of a term sheet shared with The Logic. The project was never executed.

As he continued selling customers on the promise of Attabotics’ technology, Gravelle seemed unfazed by its technical limits, according to four people with knowledge of his efforts to expand the business. Hardware and software engineers’ concerns about the stability and performance of the product went unaddressed, three people said. Gravelle pushed to “keep the company moving forward at all costs,” a former employee said, adding that there was a sense inside the firm “that we were overselling and under-delivering.”

Meanwhile, communication with investors became more guarded following the company’s US$50-million Series C fundraising in 2020, backed by Honeywell and the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan’s venture capital arm.

After the round, management stopped providing investors with any information aside from financial statements, declining to offer context on business decisions, for example, or explain its broader corporate philosophy, according to one source. Following its Series C1 in 2022, when it raised US$71.7 million, Attabotics adjusted its shareholder status so that it only had to supply financial documents to shareholders with major stakes—a decision that one person called an effort to “restrict view of the company.” Two sources said that the firm did not hold annual meetings with all shareholders.

Some who raised dissenting opinions about Attabotics’ decisions didn’t remain in their positions of influence, one source said. SeeHon Tung, then managing director of Werklund Family Office, a Calgary-based investment firm, was among the most outspoken critics of the company’s decisions in his role as a board observer, three people said. In 2020, he left that position. It was not an atypical outcome, said one person with knowledge of the turnover on Attabotics’ board at the time: “These guys would ask really pointed questions about spend and performance, and they’d be pushed off the board.”

Despite Attabotics’ communication style and its technological struggles, Crown-owned and taxpayer-funded organizations remained some of the startup’s most eager backers. Export Development Canada, the Business Development Bank of Canada, the Strategic Innovation Fund and the Opportunity Calgary Investment Fund all supported the firm through loans, grants, revolving credit facilities and equity.

As of the bankruptcy filing, Attabotics owed EDC around $41 million in convertible promissory notes. BDC and Western Economic Diversification Canada were owed $2.8 million and $2.5 million, respectively, making those Crown corporations the company’s three largest secured creditors.

Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and its VC arm, Teachers’ Venture Growth, were also major Attabotics’ investors, participating in both the company’s Series C and Series C1 rounds in 2020 and 2022.

On March 15, 2023, the company was hit with arguably its biggest setback when a fire broke out in an Attabotics system installed at a Canadian Tire distribution centre in Brampton, Ont. Canadian Tire was using the system to sort auto parts, one person familiar with the operation said.

This time, flames spread through the warehouse, destroying loads of inventory and costing the retailer $74.6 million in quarterly earnings. It was the second time Attabotics’ system had caught fire in the Canadian Tire warehouse, after its “proof-of-concept” system started a much smaller blaze in August 2021.

Attabotics alleged that Canadian Tire’s fire alarm failed to go off, and that its employees were forced to flee the warehouse, one by one, through the front entrance turnstiles.

Attabotics blamed Canadian Tire for the 2023 incident and filed a lawsuit against the retailer two months later in Ontario Superior Court. In it, Attabotics claimed $32.5 million in damages, alleging that Canadian Tire’s “gross negligence, wilful misconduct” and “recklessness” had caused the blaze. The Calgary startup claimed that the fire had caused reputational damage, lost profits and missed business opportunities.

In its claim, Attabotics said the fire started in a bin transporting brake pads, a steering pump and other automotive products. At some point, the suit alleged, a Canadian Tire employee added a “foreign fire hazard or ignition source” that likely caused the fire. “The swiftness with which the initial fire ignited indicates that an improper material was placed in the relevant bin,” the company said. It also alleged that Canadian Tire’s fire alarm had failed to go off, and that some emergency exits in the facility were locked, forcing Attabotics’ employees to “flee one-by-one out of the turnstile front entrances of the Brampton warehouse.”

Canadian Tire denied Attabotics’ claim that its employee had placed hazardous or flammable products in the bin that caught fire. Further, none of the items the robot was carrying “contain any electricity, combustible fluids or other sources of fuel that would have been capable of igniting the fire,” it said in its legal response.

The retailer was also aware of the 2021 Nordstrom fire, and said the incident was “strikingly similar” to the fire that broke out four months later in its own warehouse. Canadian Tire noted that an Attabotics’ robot was to blame for the Nordstrom fire, pointing to the startup’s own investigation that traced the source to a faulty module in the system’s battery chargers that caused a sudden spike in voltage, from 86 volts to 140 volts. Attabotics then failed to make the necessary improvements to stop the second, larger fire from igniting, Canadian Tire alleged.

“After an investigation of the [proof-of-concept] fire, Attabotics told Canadian Tire that they had implemented a solution that would prevent a similar incident from reoccurring. Attabotics lied.

The two companies reached a settlement in February 2024, with Canadian Tire stating publicly that the cause of the fire was never found. One former Attabotics employee who spoke to The Logic said they believed Attabotics’ claim was accurate, based on the company’s own investigation of electrical currents, voltages and other data during the fire’s ignition. Ladd said he spoke to Gravelle after the fire. “The way he described it, in all honesty, legitimately sounded like Attabotics was not at fault,” Ladd said.

Around the time the Canadian Tire fire broke out, though, Attabotics was ensnared in another customer lawsuit, this time with Indiana-based supply chain and logistics firm Bastian Solutions.

The Bastian operation also suffered technical complications, which the U.S. company detailed in a lawsuit filed against Attabotics in February 2023. Under a 2020 agreement between the two firms, Attabotics had authorized Bastian to resell its robotics tech to end users. By December of that year, Bastian had negotiated a deal with media logistics firm Accelerate360 (A360), which later installed Attabotic’s system in its 716,000-square-foot warehouse in Kansas.

In July 2022, A360 filed a lawsuit against Bastian in Delaware Superior Court, alleging that Attabotics’ system had failed to operate as promised. Bastian in turn sued Attabotics, citing A360’s claim that there were “a host of ‘catastrophic’ issues with the Attabotics nest, ants and software.” (The “nest” refers to the structure in which the robots move.)

According to A360, Bastian broke its contract with the company due to a “failure to meet the approved project schedule, and for breach of representations”—claims Bastian effectively passed on to Attabotics in its lawsuit against the Calgary startup.

According to Bastian’s complaint, filed in the Indiana District Court, A360 told the company “that Attabotics was not forthcoming with what it was doing to the system, that Attabotics negligently updated the software to a version which made the system unworkable, and that Attabotics staff failed to show up” at site. The combination of shortfalls shut down A360’s operations, the document alleges.

In his verdict at the end of 2024, Indiana District Court Judge James Sweeney ultimately sided with Attabotics, ruling that Bastian had “failed to show by a preponderance of evidence” that the company breached its contracts or warranties.

While the decision marked a win for Attabotics, it had to fight the legal battle amid mounting financial strain. By the end of 2024, the firm’s struggles were evident in its bottom line and were made worse by the hangover of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lockdowns initially kicked off an e-commerce craze that jump-started logistics firms, but there were after-effects: supply chain disruptions and, later, a spike in interest rates and a decline in consumer spending. In an affidavit filed as part of Attabotics’ bankruptcy proceedings, board chair Edna Conway cited those pressures as reasons for the company’s deteriorating finances, saying that customers subsequently delayed warehouse investment plans.

According to the affidavit, annual revenue plunged from $11.4 million in 2022 to just over $3 million in 2024, a meagre figure considering the $200 million it has raised. Meanwhile, costs were ballooning. Over that period, research and development expenditures alone totalled about $76 million, while debt and interest payments in 2024 surpassed revenues, according to financial statements. All told, the company’s annual losses reached $35 million by 2022, then soared to $49.5 million in 2024.

Attabotics’ current book value is $31.6 million, while its liabilities total $73.8 million, according to the affidavit.

In late 2024, Attabotics tried to start a Series D funding round, but existing shareholders raised concerns about the company’s cash flows, Conway said in her affidavit. That caused a “ripple effect across the investor community” and made it impossible for the company to deliver on its remaining orders, Conway said.

By July 2025, after filing for creditor protection, the company had begun seeking a buyer for its remaining assets, which included what Conway called a “highly valuable suite of intellectual property.”

In late July, The Logic reported that Honeywell had expressed interest in acquiring Attabotics in 2020 for US$350 million. Sources could not specify why the deal never went through, but the bid illustrated how far the company had fallen from its previous heights.

Gravelle, at least in his public-facing communications, seemed to ride Attabotics’ stomach-turning descent with an upbeat demeanor. As recently as early 2024, he starred in a video the company posted on YouTube, extolling the system’s strengths with little hint of its operational problems, or the financial crisis already on Attabotics’ horizon.

Attabotics Rejected a $350M Offer Before Collapse

Honeywell expressed interest in acquiring the Calgary robotics startup in a 2020 all-cash deal. Today, Attabotics is in creditor protection.

In a revealing investigation by Jesse Snyder of The Logic, it has come to light that Honeywell—one of Attabotics’ most prominent investors—attempted to acquire the Calgary-based warehouse robotics startup in 2020 for US$350 million in an all-cash deal. The offer was made via a non-binding expression of interest, according to internal documents reviewed by The Logic, but the deal was never finalized.

Fast forward to July 2, 2025: Attabotics filed for creditor protection, laying off nearly 200 employees and initiating proceedings to liquidate its remaining assets.

This sharp reversal of fortune underscores how far the once-promising Canadian startup has fallen. Founded in 2016 by CEO Scott Gravelle, Attabotics developed a vertical, cube-based robotic fulfillment system that drew major interest from investors and clients alike. Its technology, which allowed robots to move in 3D space to store and retrieve goods, promised to save retailers significant warehouse space.

Over the years, Attabotics raised nearly US$200 million from a roster of high-profile backers including Comcast Ventures, Forerunner Ventures, the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan (via its venture arm), and Honeywell. It also received funding from several Canadian government bodies, including Export Development Canada, BDC, the Strategic Innovation Fund, and the Opportunity Calgary Investment Fund.

Honeywell’s proposed acquisition came a year after its first investment in Attabotics, and just months before it participated in the company’s US$50-million Series C round. According to The Logic, the offer was directed to board members at Forerunner and Comcast Ventures, and was described by Honeywell as “strategically compelling,” allowing it to extend its services across the fulfillment supply chain.

But for reasons that remain unclear, the deal never materialized. Sources close to the situation were unable to confirm whether the offer was rejected by the board or withdrawn by Honeywell. Neither company commented for the story.

By 2022, Attabotics authorized new shares valued at nearly US$181 million as part of a fresh fundraising effort. But by 2025, the company had collapsed under mounting debt—its liabilities now total US$73.8 million, while the book value of its remaining assets, including IP, sits at US$31.6 million.

A cautionary tale in Canada’s tech sector, Attabotics’ story highlights the volatility of deep-tech ventures—and the narrow window for strategic exits.

📰 Full story by Jesse Snyder available at The Logic Source Article: https://thelogic.co/news/exclusive/attabotics-honeywell-bid/

Attabotics filed for insolvency after Export Development Canada sought to enforce security over assets

Calgary robotics startup Attabotics Inc. filed under Canada’s bankruptcy act last week after its largest secured creditor, Export Development Canada, sought to enforce its security over the company’s assets, according to documents filed with an Alberta court.

The insolvent company, now down to nine non-executive employees after laying off 192 of its 203-person staff and suspending most of its operations on June 30, is now soliciting options to sell its assets or business over the next month after it failed to raise financing that would have enabled it to fund a spate of new business.

Attabotics last Wednesday filed an intention to make a proposal under the Federal Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act, and two days later received approval from Justice John Gill of the Court of King’s Bench of Alberta to obtain $1.5-million in interim funding from EDC, its largest secured creditor. The company had previously raised $220-million in financing from backers including EDC, Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan Board, Coatue Management and Comcast Ventures plus $34-million from the federal Strategic Innovation Fund.

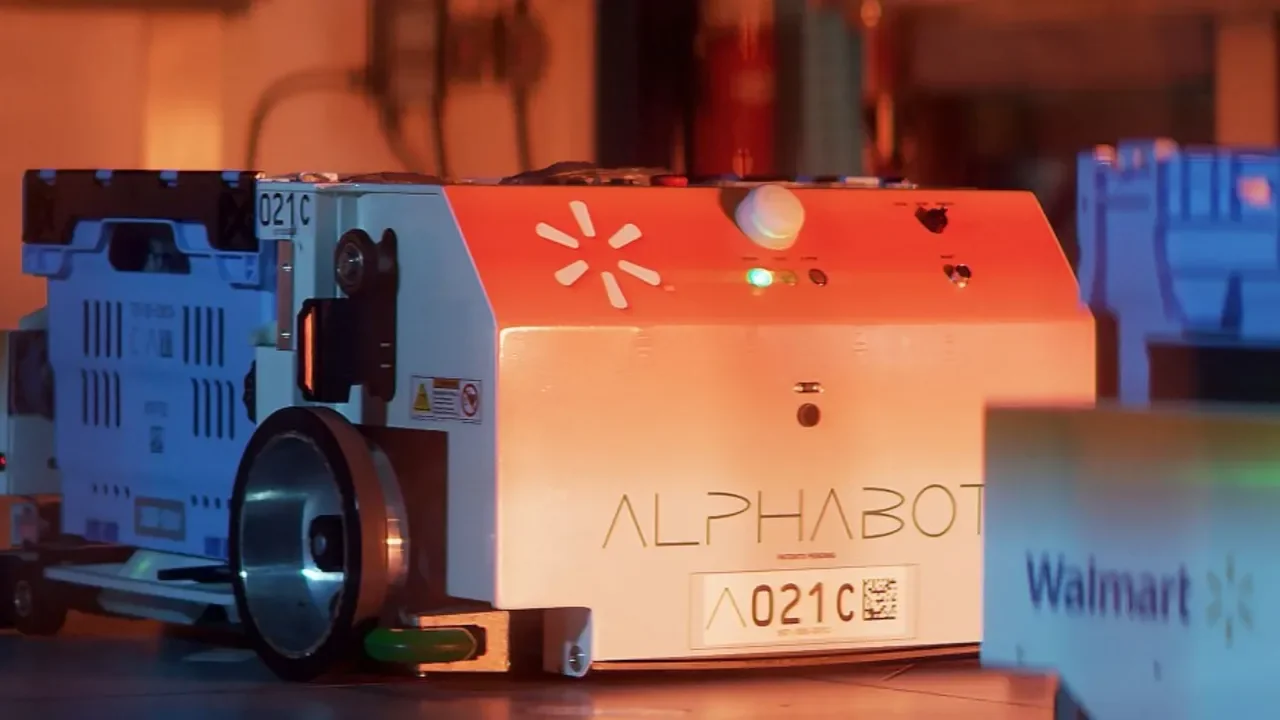

Attabotics, incorporated in 2016 and founded by CEO Scott Gravelle, made automation equipment used to fulfill orders that transforms product warehouses into high-density, vertical and scalable storage structures inspired by ant-colony frameworks. Instead of moving goods from aisle to aisle, Attabotics robots move up and down vertical structures, grabbing goods with extendable arms, then bringing them back to workers who prepare them for packing and shipping.

Attabotics chair Edna Conway said in a sworn affidavit that after spending tens of millions of dollars annually on research and development, the company in late 2022 attempted to accelerate deployment of its robotics warehousing system to new industries, customers and markets around the world. E-commerce had surged as consumer spending shifted online during the pandemic.

The company worked at several sites across North America with customers such as Canadian Tire, Gordon Food Services, Pan Pacific Pet and Modern Beauty Supplies.

While revenue reached $11.4-million in 2022, “revenues began to sharply decline” as interest rates shot up, constraining consumer spending and lowering demand for e-commerce, Ms. Conway wrote. That led some customers to delay planned projects with Attabotics, and revenues plummeted to $8-million in 2023 and $3-million in 2024.

Last year the company amassed $44.4-million in operating expenses and lost $49.3-million. In the first quarter of 2025 Attabotics generated just $800,000 in revenue and had $11.2-million of operating expenses, losing $12.5-million and ending the quarter with $6.3-million of cash and equivalents, down from $13.6-million a year earlier.

Ms. Conway wrote the business did begin to stabilize by late 2024, resulting in $30-million of new business to be delivered in 2025 and 2026. That included a supply agreement signed with British grocery conglomerate Tesco.

But when Attabotics tried to raise new capital to finance the orders, investors “expressed concern with the applicants’ cash flow challenges and elected not to participate in further financings,” she wrote, which caused a ripple effect across the investor community. That prompted the company to shelve financing efforts, which meant it couldn’t proceed on delivering on the orders “on the planned schedule,” she wrote.

By the time EDC served Attabotics with a notice of intention to enforce security on June 18 – triggering a 10-day waiting period before the agency could proceed – the company was already in discussions with various parties regarding the sale of its business or assets – including 150 granted and pending patents. The new money from EDC “is only sufficient to fund the applicants’ business for a period of 30 days on a massively scaled down basis,” Ms. Conway wrote.

In an e-mailed statement, EDC spokesman Louis-Antoine Paquin said the federally owned export finance business “has been a significant supporter to Attabotics. Over the past three years, EDC has provided both investments and financing to the company to support their Canadian manufacturing technology and supply chain ambitions. EDC’s support for Attabotics has been crucial for the company, enabling it to mature their technology while staying Canadian. EDC is providing financing support to Attabotics in support of its court approved restructuring process.”

The company’s three largest secured creditors are all federal Crown corporations or agencies: EDC is owed $46.3-million, followed by Business Development Bank of Canada, owed $2.8-million, and Western Economic Diversification Canada, which is out $2.5-million. The company has 131 secured creditors in addition to past and present employees.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this story stated that Export Development Canada pushed Attabotics toward insolvency. In fact, EDC served the company with a notice of intention to enforce security on June 18, an action under the Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act by which a secured creditor informs an insolvent entity that it intends to enforce its security over the entity's property, thus preserving its rights. That triggers a 10 day waiting period before the creditor can take any action. The story has been udpated.

Source: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-export-development-canada-463-million-attabotics-creditor-protection/ (July 7, 2025)

Our Thoughts:

While revenue reached $11.4 million in 2022, Attabotics' sales sharply declined in the following years—dropping to $8 million in 2023, $3 million in 2024, and just $800,000 in Q1 2025. Operating expenses remained extremely high, with $44.4 million spent in 2023, leading to a $49.3 million annual loss, and $12.5 million lost in Q1 2025 alone.

These numbers suggest Attabotics likely invoiced two ASRS systems in 2022, one or two in 2023, one (likely very small) in 2024, and none booked so far in 2025. For a company that raised over $250 million, this level of commercial output was alarmingly low.

Yet just earlier this week, CEO Scott Gravelle made claims that Attabotics:

*Had $60 million in pipeline sales from Tesco, Gordon Food Service, Modern Beauty Supplies, the U.S. Department of Defense, and The RealReal

*Had recognized $37 million in revenue in 2025.

*Was on track to generate $100 million in 2026.

These statements are completely inconsistent with court filings and actual performance. They appear to be fabricated figures, misleading stakeholders with projections pulled out of thin air—like a magician producing coins from behind an ear.

Unfortunately, this type of behavior is common in the automation and robotics space. Many vendors routinely exaggerate their current sales, customer base, projected pipeline, and system capabilities, just as many are now overhyping vague claims of being "AI-enabled."

It’s worth pointing out that Attabotics repeatedly claimed to be the only 3D ASRS system in the world, describing their platform as “the first and only 3D robotics supply chain system.” These statements were grossly misleading.

For example, Exotec, a well-established ASRS provider, also operates a 3D ASRS system—its Skypod robots move vertically and horizontally within a racking system, offering true three-dimensional storage and retrieval capabilities. Exotec’s system was commercially deployed years before Attabotics reached full-scale production.

Claims of being the "only" 3D solution not only ignored existing competition but also distorted the landscape of ASRS innovation, where multiple vendors were already delivering multi-dimensional automation solutions at scale.

It’s unfortunate that major organizations like Tesco, Gordon Food Services, Modern Beauty Supplies, the U.S. Department of Defense, and The RealReal likely made high-risk purchasing decisions without conducting deeper technical and commercial due diligence. Each of these companies would have gained significant value by engaging an experienced and truly independent consultant—someone capable of separating bold marketing from operational reality.

Now, there’s a very real risk that the Attabotics systems already deployed will become ‘boat anchors’—expensive, unsupported hardware with no upgrade path—and will ultimately be decommissioned, leaving behind sunk costs and stranded operations.

hashtag

Stuck on a Critical Automation Project? Bring in the Experts — Instantly.

Whether you’re blocked on a brownfield retrofit, launching a greenfield site, or navigating a complex digital transformation, our expert advisors are ready to step in and help.

Work directly with senior consultants—former executives and technical leaders from Amazon, Walmart, and other Tier 1 supply chain operations. Book them by the hour or by the day. No long-term contracts. Just clarity and results.

Overview: Attabotics Files for Bankruptcy Protection

Attabotics Inc., a Calgary-based robotics and automation startup known for its innovative 3D vertical storage and retrieval system, filed for bankruptcy protection on June 30, 2025, according to multiple reports.

Founded in 2016 by CEO Scott Gravelle, Attabotics aimed to disrupt traditional warehouse fulfillment by eliminating aisles in favor of a cube-based, goods-to-person architecture inspired by the structure of ant colonies. The company's robotic "blades" operated on X, Y, and Z axes, fetching inventory bins stacked vertically inside a dense, modular cube.

At its peak, Attabotics employed over 300 people, with roughly 250 based in Calgary as of 2022. It was one of Canada’s most high-profile deep-tech ventures, widely promoted as a potential global leader in supply chain innovation.

However, the recent filing of a Notice of Intention to Make a Proposal under Canada's Bankruptcy and Insolvency Act reveals a sharp reversal of fortune. A sign posted at the company's facility near Calgary International Airport indicated that employee contracts were terminated effective June 30, and staff access to the premises was revoked. Some employees were seen leaving with personal belongings, exchanging quiet farewells.

Former staff began updating LinkedIn profiles with “Open to Work” statuses, and Gravelle’s personal bio was changed to read: “Recovering visionary. Taking a long-deserved break.”

Attabotics had raised over US$165 million between 2019 and 2022, including a US$71.7 million Series C-1 round, and received millions in public support from the Strategic Innovation Fund and the Opportunity Calgary Investment Fund.

Despite early promise, the company faced persistent technical and commercial headwinds that it ultimately could not overcome.

What Went Wrong

As seasoned professionals in the warehouse automation and robotics industry, our team has closely followed Attabotics' journey. While many will attribute the company’s downfall to market conditions or capital exhaustion, we believe the failure was largely the result of avoidable strategic and executional errors.

1. Suing a Key Customer: Canadian Tire

One of the most damaging decisions, in our opinion, was Attabotics’ decision to sue Canadian Tire Corporation after a major fire at the Brampton distribution center. This occurred during a joint Scale AI–funded project in which Attabotics had received $7 million to help redesign and assist Canadian Tire’s warehouse operations.

The fire caused $87.7 million in losses. Instead of working toward a collaborative solution with a major retail client, Attabotics took an adversarial approach—accusing the customer of “wrongful conduct.” This move likely shattered customer trust and sent negative signals to investors and other prospects.

2. Lack of Domain Expertise at the Executive Level

Founder and CEO Scott Gravelle lacked hands-on experience in key operational areas such as robotics engineering, supply chain systems, ASRS design, or warehouse sales. His vision was bold, but the absence of practical domain knowledge hindered the company's ability to make the right product, engineering, and go-to-market decisions.

You cannot lead a company selling mission-critical warehouse technology without deeply understanding what warehouse operators actually need—or how they think.

3. Lavish Spending on Facilities Instead of Core Capabilities

Attabotics spent millions building an elaborate, Taj Mahal–inspired headquarters in Calgary. While architecturally impressive, this investment came at a time when customers were still questioning the system’s reliability and throughput. It sent the wrong message: that the company prioritized optics and media attention over customer results.

In automation, the most beautiful building in the world won’t matter if your system fails to meet its SLA.

4. Internal Culture of Inexperience and Echo Chambers

Attabotics’ leadership team, in our view, was filled with executives and managers who lacked the operational experience needed to sell, support, and scale complex robotics systems. Many were “yes-man” types who did not challenge key decisions.

Making matters worse, most of Attabotics’ customers were first-time buyers of automated systems—inexperienced in selecting, operating, or scaling highly complex warehouse technologies. This placed enormous pressure on Attabotics to deliver flawless performance without experienced internal leadership or mature client-side counterparts.

5. Failure to Deliver Reliable, High-Speed Software

This may be the most critical issue of all. Attabotics never succeeded in developing the software required to operate their hardware at the speed, reliability, and precision required in automated storage and retrieval systems (ASRS).

Despite their novel 3D hardware concept, the orchestration layer lacked the maturity to match the real-world throughput and reliability of competitors like AutoStore and Exotec, both of which offer battle-tested, production-grade platforms in active use globally.

In warehouse automation, software is the brain—and without robust, latency-free software, even the most innovative hardware becomes a liability.

Final Thoughts

Attabotics had a compelling story: visionary hardware, vertical storage innovation, and early praise from media and investors alike. But vision without execution—and innovation without discipline—rarely scale in the industrial world.

The fall of Attabotics serves as a stark reminder that in the supply chain sector:

🚫 Trust is fragile.

🔧 Execution is everything.

⏱️ Throughput and reliability are non-negotiable.

🤝 Relationships matter more than hype.

Warehouse automation is not a world that tolerates shortcuts. It rewards those who understand the market deeply, build resilient systems, and support customers through years of operational maturity—not just press releases.

Should Amazon Acquire Attabotics? A Strategic Move Hiding in Plain Sight

Following Attabotics' recent bankruptcy protection filing, the Canadian robotics company’s intellectual property, hardware, and remaining assets are reportedly available for just $30 million USD. This is a stunning discount for a company that once raised over $165 million and claimed it could redefine warehouse fulfillment.

But for the right buyer, these assets could offer not just a salvage opportunity—but strategic leverage.

My take: Amazon should seriously consider acquiring Attabotics.

Why Attabotics Still Matters—Even in Bankruptcy

Attabotics’ value was never in its revenue or client base. It was in its core architecture and the bold attempt to build a truly vertical, cube-based ASRS system.

While execution fell short, the underlying concept remains compelling—especially for a company like Amazon.

Attabotics’ system was designed to:

- Eliminate traditional aisles.

- Store inventory in a compact vertical cube.

- Use robotic “blades” that move in X, Y, and Z axes.

- Operate within smaller warehouse footprints (ideal for urban environments).

And critically: This approach aligns directly with Amazon’s push toward automated micro-fulfillment hubs closer to Prime customers.

What Attabotics Got Wrong: Software and Orchestration

As someone working in warehouse automation, I believe the biggest failure at Attabotics wasn’t the hardware—it was the software.

Despite years of funding and media attention, the company never succeeded in building:

- A robust middleware orchestration layer.

- A scalable fleet management and navigation engine.

- A real-time inventory and order routing system.

This software gap meant the system could never achieve the speed or reliability of AutoStore or Exotec. But here’s the point: Amazon doesn’t need Attabotics’ software. They already have world-class engineering talent and internal fulfillment orchestration platforms.

Why It Makes Sense for Amazon

1. Strategic Fit for Micro-Fulfillment

Amazon has spent the last two years testing compact, cube-based storage systems. The Attabotics platform fits neatly into this ongoing experimentation.

2. The Entire Company for the Cost of Two Systems

AutoStore systems typically cost $10–20 million. For $30 million, Amazon could acquire 100% of Attabotics’ assets.

3. R&D Shortcut and IP Defense

Even if Amazon never rolls out the system, owning Attabotics IP prevents competitors from leveraging it and adds defensive patents.

Tesco’s Move: A Subtle Vote of No Confidence in Attabotics Software

While Attabotics’ bankruptcy has captured headlines, many may have missed an important footnote: UK retail giant Tesco recently entered into an agreement with Attabotics to pilot a micro-fulfillment center (MFC) using its cube-based hardware platform.

Tesco reportedly committed to evaluating a single pilot installation, with the potential for up to 70 additional sites across the UK. But what’s telling: Tesco decided to purchase the hardware—but refused to use Attabotics’ software.

Instead, Tesco’s team chose to develop their own orchestration and control systems—a rare move for a retail giant.

As someone deeply involved in automation systems, I see this decision as a damning indictment of Attabotics’ software platform. In my opinion, this failure falls squarely on Scott Gravelle’s leadership. A decade after founding the company, Attabotics had still not delivered a software system trusted by tier-one customers.

Final Thought

For a company of Amazon’s scale, $30 million is a rounding error. But in the digital retail war to offer customers ever faster delivery options, it could buy them a massive head start on cube-based next-generation automated micro-fulfillment infrastructure

Attabotics may have failed as a company. But its core idea—dense, vertical, modular fulfillment—remains highly relevant. With the right engineering team and orchestration brain behind it, it could still become a valuable tool in Amazon’s ever-expanding automation playbook.

A letter taped to the employee entrance at Attabotics in northeast Calgary is shown on Wednesday, July 2, 2025. The company is making a notice to file for bankruptcy. Jim Wells/Postmedia

A letter taped to the employee entrance at Attabotics in northeast Calgary is shown on Wednesday, July 2, 2025. The company is making notice that it intends to make a proposal under the bankruptcy and insolvency act. Jim Wells/Postmedia