Zebra Unwinding Fetch Robotics — A Cautionary Tale for Automation Customers

Zebra Technologies is in the process of exiting the autonomous mobile robot space, unwinding the business that emerged from its acquisition of Fetch Robotics several years ago. While the precise path forward has not been publicly finalized — whether through divestiture or an orderly wind-down — the strategic direction is evident: mobile robotics is no longer a priority area for Zebra.

What makes this notable is that the decision did not come after a period of neglect. Zebra continued to support and expand the Fetch portfolio well beyond the acquisition, rolling out new robot models, extending its software offerings, and positioning AMRs as part of a broader, tightly integrated warehouse solution that included wearables, analytics, and execution software. Customers even reported tangible productivity gains in recent deployments.

Despite those efforts, the business failed to reach the scale or differentiation required to justify continued investment.

Even massive scale and brand power weren’t enough

What makes this outcome particularly instructive is that Fetch was not an underfunded startup struggling for relevance.

Fetch had the backing of Zebra Technologies — one of the most established brands in supply chain technology — along with global sales reach, deep enterprise relationships, and the ability to bundle robotics into broader warehouse solutions. If any AMR business had structural advantages to succeed at scale, this was it.

Despite that, Fetch was unable to break through an intensely crowded automation market offering end users hundreds — if not thousands — of competing robotic and software solutions. That reality alone should give the industry pause.

Have AMRs now been commoditized?

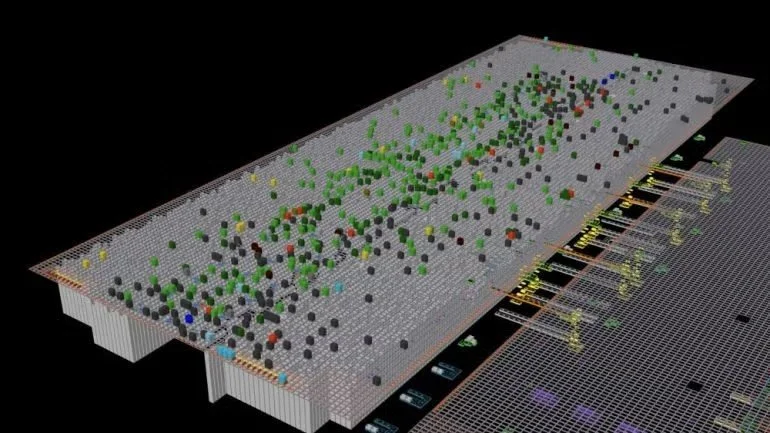

Autonomous mobile robots have rapidly commoditized. Anyone who attends ProMat or CeMAT can see it clearly: long rows of vendors offering robots with similar form factors, similar navigation capabilities, and largely overlapping use cases.

As hardware converges, margins compress, sales cycles lengthen, and sustained differentiation becomes increasingly difficult. For a public company like Zebra, this makes the economics of scaling an AMR business far less compelling.

A failure of problem definition

The issue at Fetch was not robotics capability.

The deeper challenge was the inability to clearly define the specific problems customers were trying to solve — or how Fetch’s AMRs and software meaningfully differentiated from other established AMR offerings, such as Locus Robotics.

From the customer’s perspective, many AMR solutions now appear interchangeable:

Similar robots

Similar picking and transport workflows

Similar productivity claims

Similar ROI narratives

Without a sharply defined problem statement and a defensible operational advantage, differentiation quickly collapses into feature comparisons and pricing pressure.

Competitors like Locus Robotics succeeded by anchoring their platform around a clear, repeatable use case and deployment model that customers could immediately understand.

By contrast, Fetch and Zebra increasingly broadened scope — more robots, more workflows, more software layers — without clearly answering why customers should choose this solution over the many alternatives already available.

The unproven “fewer robots” promise — and the lock-in strategy behind it

A central pillar of Zebra and Fetch’s positioning was the claim that advanced software capabilities would allow customers to deploy fewer robots than competing AMR solutions — delivering faster ROI and quicker profitability.

In theory, this was an appealing message. In a commoditized hardware market, software-driven efficiency should be where differentiation emerges.

In practice, this claim was never meaningfully substantiated. There were no transparent benchmarks, no side-by-side throughput comparisons, and no published evidence showing materially higher productivity per robot relative to other mature AMR platforms.

To an experienced robotics or warehouse automation professional, the message often sounded aspirational rather than engineered. Without rigorous proof, “fewer robots” reads more like a marketing construct than a defensible system-level advantage.

More importantly, this narrative was inseparable from a broader vendor-lock-in strategy.

Zebra positioned these performance gains as achievable only within a tightly integrated, Zebra-branded ecosystem — robots, software, wearables, analytics. Faster ROI became a function of exclusivity.

That approach increasingly conflicts with how customers think about automation today.

End users are actively trying to reduce dependency on single vendors, not deepen it. They want flexibility — the ability to introduce new robots, swap vendors, and evolve automation strategies over time without being constrained by proprietary software boundaries.

When performance claims cannot be independently validated and require ecosystem lock-in to deliver value, skepticism is inevitable.

The uncomfortable reality: AMRs are often slower than existing workflows

Another fundamental issue AMR vendors must confront is a simple operational reality: AMRs are often slower than the workflows already used in most warehouses today.

This is rarely stated openly, but it is well understood by experienced operators.

Take forklifts as an example. Autonomous forklifts are typically far slower than human-operated reach trucks from vendors like Raymond or Crown. Human drivers move faster, adapt instantly to dynamic environments, and operate efficiently in tighter aisles. AMR forklifts, by contrast, require wider aisle clearances, stricter safety envelopes, and conservative motion planning — all of which reduce throughput.

The same applies to picking-assist AMRs. In many traditional warehouses, an experienced human picker following a well-designed pick path is simply faster than a robot-assisted workflow that must coordinate navigation, stopping, confirmation, and exception handling.

This creates a persistent mismatch between customer expectations and operational reality.

There is a widespread — but incorrect — assumption that robots must be faster than humans to justify deployment. In practice, speed is often the wrong metric.

AMRs deliver value elsewhere:

Labor availability and stability

Predictable, repeatable throughput

Reduced fatigue and injury

Extended operating hours

Consistency at scale

When AMR vendors frame their value proposition around speed superiority, they set themselves up for disappointment. The real value lies in system resilience and reliability, not raw cycle-time comparisons.

This reality further undermines claims such as “fewer robots” or “faster ROI,” especially when those claims are not grounded in transparent system-level data.

The closed-ecosystem problem

Zebra’s attempt to move up the stack through tightly integrated fulfillment software reinforced these challenges.

That approach may have worked in the past, when automation vendors could plausibly “own” a customer or a portion of the warehouse. That era has passed.

Today’s warehouses operate mixed environments: AMRs, ASRS, sortation, pallet automation, forklifts, goods-to-person systems, and human labor — often sourced from multiple vendors.

End users now expect:

Freedom to mix and match robots

Fast onboarding of new vendors

Interoperability across systems

Protection from vendor lock-in

A closed ecosystem, regardless of polish, increasingly works against these expectations.

Why this won’t be the last AMR exit

Zebra’s decision is unlikely to be an isolated event.

The AMR market is crowded, capital-intensive, and unforgiving. Hardware alone is no longer a moat. Software tightly coupled to proprietary hardware isn’t one either.

What customers increasingly value is orchestration, integration, and operational flexibility — systems that allow many robots to work together rather than forcing exclusivity.

This shift will likely result in:

Further consolidation

More divestitures

More robotics companies discovering that scale is harder than expected

Fetch’s legacy still matters

None of this diminishes Fetch’s role as an early AMR pioneer.

Founded in 2014, Fetch helped shape how mobile robots entered warehouses and fulfillment centers. Many of the people and ideas behind Fetch will continue influencing the robotics industry through new companies, platforms, and roles.

A critical takeaway for customers: start with software, not robots

The Zebra–Fetch outcome also highlights a critical lesson for end users — one that often gets overlooked in early-stage automation decisions.

Before purchasing a first AMR, customers should assess their software architecture, not just the robot itself.

Too many automation projects begin with hardware selection and only later confront the complexity of integration, orchestration, and long-term control. By then, software choices are often implicitly dictated by the robot vendor.

A more resilient approach is to first adopt a vendor-neutral, independent execution layer — one that is not tied to any single automation provider.

This layer should be capable of communicating across the existing enterprise stack:

ERP

WMS

WCS

WES

and act as the system responsible for execution, coordination, and exception handling across all automation assets.

By decoupling execution logic from hardware vendors, customers retain long-term control. New robots can be introduced, legacy systems can coexist, and future brownfield or greenfield projects can be integrated without re-architecting the operation or being forced onto a single vendor’s roadmap.

In an environment where automation technologies evolve rapidly — and vendor strategies can change unexpectedly — architectural independence is no longer theoretical. It is practical risk management.

The bigger lesson

The lesson from Zebra and Fetch isn’t that AMRs don’t work.

They do.

The lesson is that owning the robot is no longer the same as owning the operation.

Warehouses have evolved. Customer expectations have changed. And the next generation of winners will be those who prioritize software architecture, orchestration, and long-term control — enabling robots, systems, and people to work together without being constrained by vendor boundaries.

That ship has sailed.

AutoStore reported its 2025 results this week, outlining a year that moved from early caution to clear second-half acceleration.