American Eagle Closing Three Automated Facilities Amid Fulfillment Challenges

When Automation Outgrows Its Original Operating Model

American Eagle’s decision to wind down three Quiet Logistics fulfillment centers has understandably drawn attention. On the surface, the move has been framed as a strategic refocus on core brands, with Quiet’s third-party services set to discontinue over the coming months and operations in Boston, Dallas, and La Palma closing by mid-2026. Atlanta will continue to support American Eagle brands.

What’s worth examining more closely, however, is how this outcome came to be.

Because this is not a simple case of automation underperforming.

Quiet Was Already a Proven Operator

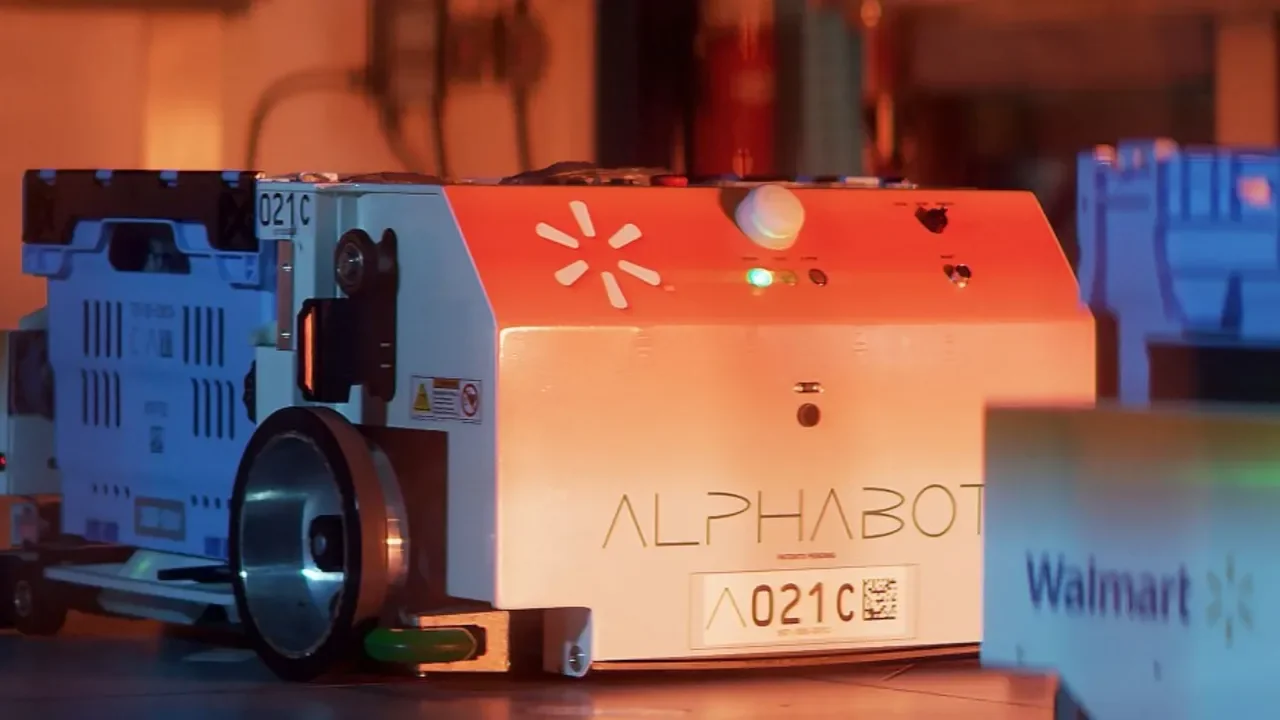

Before its acquisition, Quiet had built a strong reputation as a third-party logistics provider. Its fulfillment model, operating discipline, and customer relationships were already established, and its infrastructure supported reliable multi-client operations.

After the acquisition, the strategic intent evolved.

Quiet’s network was increasingly used to support American Eagle’s own store replenishment and e-commerce operations, while also offering excess capacity to external retailers. In theory, this hybrid model promised the best of both worlds: internal optimization with incremental third-party revenue.

In practice, it introduced a new set of requirements.

A Shift in Business Model Requires a Shift in Engineering

Operating fulfillment centers for a single enterprise brand is fundamentally different from running them as a hybrid network supporting multiple demand profiles.

Once Quiet’s role expanded, the facilities required:

Re-engineering of workflows

Changes to software, controls, and integrations

New capacity-management and prioritization logic

Greater flexibility to handle mixed and competing demand

These are not incremental tweaks. They require ongoing engineering ownership, long-term systems thinking, and the ability to continuously redesign how automation assets are orchestrated — not just operated.

This is where many logistics operators encounter friction, particularly when automation is built around proprietary, tightly coupled orchestration layers that limit change outside the original design envelope.

Retail organizations are exceptional at merchandising, brand management, and customer experience. Far fewer are structured to function as long-term industrial automation engineering organizations.

Automation Delivered Value — But Adaptation Was Constrained

American Eagle has been clear that Quiet’s infrastructure improved its supply chain performance:

Inventory was positioned closer to stores and customers

Delivery times improved

Costs were reduced

Those gains were real.

But extracting additional value — by expanding the model, modernizing facilities, and adapting them to support multiple fulfillment roles — required more than operational excellence. It required software-level control over how automation workflows were coordinated, reprioritized, and evolved.

Without that control, even well-performing facilities can become increasingly difficult to adapt as business requirements change.

The Orchestration Layer Is the Limiting Factor

This episode reflects a broader challenge seen across automated fulfillment operations.

Changing, refitting, or redesigning an automated facility is extremely difficult when the operator does not control the automation orchestration layer. Once workflows, priorities, and exception handling are tightly coupled to vendor-controlled systems, even modest changes to the business model can require disproportionate effort, cost, and risk.

In hybrid environments — where facilities are expected to support internal store replenishment, e-commerce fulfillment, and third-party customers simultaneously — continuous reconfiguration is unavoidable. Without ownership of the orchestration software that governs how automation assets are coordinated, those changes become slow, fragile, or simply impractical to execute.

In that context, facility shutdowns are not a failure of automation technology.

They are a consequence of operating complex automated systems without sufficient control over the software layer required to evolve them.