The AutoStore Space Fantasy

How Digging Constraints Shape Real-World Cube Storage Density and Performance

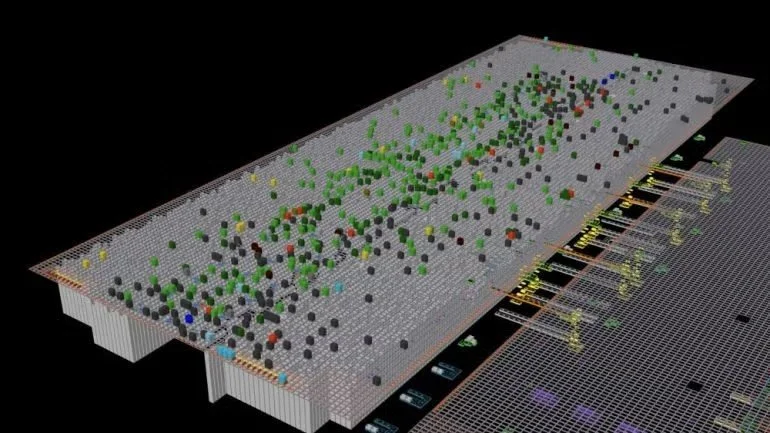

Last week, we published a comprehensive data analysis examining effective product density inside a live AutoStore customer environment. That analysis attracted significant attention across the logistics and warehouse automation community and was publicly challenged by several self-described AutoStore authorities. However, despite these objections, no empirical data, independently verifiable measurements, or alternative analysis was provided. As of today, the original findings remain unrefuted on a data-driven basis.

Approximately 66,000 bin images were analyzed from a live production system. The results are statistically robust, internally consistent, and — within the warehouse automation industry — extraordinarily rare in their level of empirical accuracy.

The findings were unequivocal:

85.8% of total bin volume was empty

More than 93% of bins were filled less than 25%

Only a negligible fraction of bins approached high utilization

This next article builds on that discussion but focuses on one narrow, unavoidable constraint that directly impacts effective storage density in AutoStore systems:

the requirement to intentionally preserve empty bin positions near the top of the grid in order to keep digging times within acceptable operational limits.

The Golden Zone — and Why It Matters

In warehousing, there is a long-established concept known as the “golden zone” — the area where products can be accessed with the least time, motion, and variability. In manual operations, this typically refers to ergonomic pick heights. In automated systems, the same principle applies, but the constraint shifts from ergonomics to access latency and predictability.

In AutoStore systems, the golden zone exists at the top of the grid, where bins can be accessed directly without digging. Bins located in this zone benefit from the lowest mechanical effort, the shortest retrieval times, and the most predictable performance.

When the Golden Zone Disappears

In traditional warehousing, the golden zone is deliberately reserved for A-class, fast-moving SKUs, precisely because it minimizes access time and variability. The same logic should apply in automated environments.

In practice, however, this principle often breaks down in AutoStore systems. While the top of the grid represents the system’s lowest-latency access zone, operational requirements frequently force operators to keep multiple top layers partially or fully empty in order to control digging times and performance variability.

As a result, many AutoStore environments are unable to consistently dedicate the top layers of the grid — the system’s theoretical golden zone — to fast-moving SKUs. Instead, high-velocity inventory is frequently stored deeper in the grid, beneath multiple bins, where access requires digging.

In effect, the golden zone does not disappear because it lacks value, but because it is repurposed as operational buffer space required to keep the system functioning.

Digging Is the Normal Case, Not the Exception

AutoStore stores inventory in vertical stacks within a fixed grid. Only the top bin of any stack is directly accessible. Retrieving any bin below the top requires temporarily removing all bins above it — a process commonly referred to as digging.

In real-world operation, most active inventory is not located at the top of a stack. As SKU counts grow and bin contents evolve, the probability that a requested bin sits beneath multiple other bins becomes the norm rather than the exception. Digging is therefore not an edge case — it is the dominant access pattern.

This behavior is not caused by poor operations or bad slotting. It is a direct consequence of the system’s physical architecture.

Why Digging Time Escalates

Digging time increases with:

Stack depth

Variability in bin placement

SKU velocity imbalance

Frequency of access to non-top bins

Each additional bin above a target bin introduces more robot movements, more handoffs, and more queueing. From a physics and queueing standpoint, this does not degrade performance linearly. Instead, deeper stacks increase variability and tail latency, particularly during peak demand.

At sufficient depth, retrieval times become unpredictable and operationally unacceptable.

The Operational Reality: You Must Leave Space Empty

To keep digging times within acceptable limits, operators must introduce intentional operational slack into the system. In practice, this means preserving empty or lightly loaded bin positions near the top of the grid, often across multiple layers.

These empty top-layer positions serve a critical purpose:

They reduce the average number of bins that must be moved during a dig

They cap worst-case retrieval times

They stabilize system performance under load

This empty space is not waste. It is required operating space.

The Density Trade-Off That Is Rarely Counted

Preserving empty bin positions at the top of the grid has a direct and unavoidable consequence: it reduces effective usable storage volume.

Theoretical density calculations often assume that the grid can be filled uniformly from bottom to top. In live systems, this assumption does not hold. A fully saturated grid dramatically increases digging times and performance volatility, forcing operators to trade space for time.

As a result, a portion of the grid must remain underutilized by design. This space:

Is operationally necessary

Grows as stacks deepen and SKU counts increase

Is typically excluded from headline density claims

The system cannot be both fully full and consistently performant.

Why This Gets Worse Over Time

This constraint does not remain static. In live AutoStore environments, the need to preserve empty top-layer bin positions typically increases over time, not decreases.

As product assortments become more dynamic — driven by online shopping, shorter product lifecycles, higher SKU churn, and long-tail inventory growth — bin contents fragment further and access patterns become less predictable. Requested bins increasingly reside deeper in the grid, increasing both digging frequency and variability.

To maintain acceptable performance under these conditions, additional operational slack is required. In practice, this often means reserving more empty or lightly loaded top-layer positions than were necessary at go-live, further reducing effective storage density as the system matures.

What This Article Is — and Is Not — Claiming

This article does not argue that AutoStore is poorly engineered, incorrectly deployed, or improperly operated. It does not rely on speculation, anecdote, or marketing comparisons.

It highlights a structural trade-off inherent to how the system accesses inventory.

The core point is simple:

Maintaining acceptable digging performance requires keeping multiple top-layer bin positions empty — and that requirement directly reduces effective storage density.

Why This Matters

Effective density determines how much product can actually be stored, how the system behaves under peak load, and how performance evolves over time. Understanding why portions of the grid must remain empty is essential to evaluating real-world performance — not just at go-live, but years into operation.

Reviewing This Analysis With Our Team

If you are operating an AutoStore system — or actively evaluating one — and would like to review this analysis in the context of your own environment, we work with operators to examine:

Actual digging behavior and bin access patterns

Effective versus theoretical storage density

How required empty top-layer space evolves over time

Where performance and density trade-offs may already be emerging

These reviews are confidential, data-driven, and system-specific, and are intended to help operators understand what is happening inside their grid beyond standard dashboards and vendor assumptions.

If you would like to review this study with our team or compare it against your own operational data, you’re welcome to reach out directly.

The AutoStore Density Claim Meets Measured Reality

For years, cube-based ASRS systems — most notably AutoStore — have been positioned as the most space-dense storage solutions available. The claim has been repeated so consistently that it is now widely accepted as fait accompli, even by competitors across the industry.

Until recently, however, no one had the empirical data required to meaningfully challenge that assumption.

That has now changed.

A third-party robotics company conducted a comprehensive, empirical study on a live AutoStore installation, using direct visual inspection to measure how storage volume was actually being utilized. This was not a simulation. Not a benchmark. Not inferred WMS or configuration data.

It was direct observation of physical reality.

Approximately 66,000 bin images were analyzed from a live production system. The results are statistically robust, internally consistent, and — within the automation industry — extraordinarily rare in their level of accuracy.

The findings are unequivocal:

85.8% of total bin volume was empty

More than 93% of bins were filled less than 25%

Only a negligible fraction of bins approached high utilization

These numbers are not debatable. They are not opinions.

They are measurements of what is physically inside the bins.

At this point, the discussion about storage density can no longer remain theoretical.

Why this experiment cannot be dismissed

In warehouse automation, most performance claims rest on assumptions: simulations, design models, or idealized operating conditions. This experiment avoids every common mechanism vendors typically rely on to deflect scrutiny.

It cannot be disclaimed by AutoStore, nor by its global dealer network, for straightforward reasons:

The data comes from a live production system

It is based on direct visual evidence, not inferred metrics

The sample size is large enough to eliminate statistical anomalies

The methodology measures physical reality, not configuration intent

The results are internally consistent across tens of thousands of bins

There is no credible counterargument to what the bins actually contain.

Disagreement remains possible — but only at the level of interpretation, not fact.

What this data forces us to confront

The immediate conclusion is not that AutoStore is “inefficient.”

That would be both inaccurate and intellectually lazy.

The real conclusion is more uncomfortable:

Theoretical density and effective density are no longer the same thing.

Cube systems may still be structurally dense by design. But under modern operating conditions, their realized density can diverge dramatically from their design promise — and the system itself provides no native mechanism to see or continuously measure that divergence.

A system designed for the 1990s, operating in the 2020s

Cube-based ASRS architectures were conceived in an era characterized by:

Stable SKU catalogs

Predictable demand patterns

Batch-oriented fulfillment

Store replenishment and wholesale flows

Delivery SLAs measured in days

That design context matters.

Today’s commerce environment looks very different:

Exploding SKU counts and long-tail assortments

Social- and influencer-driven demand spikes

Continuous order release

Same-day and next-day delivery expectations

Constant re-prioritization and re-slotting pressure

The system did not become worse. The operating assumptions changed.

Why AutoStore operators may intentionally sacrifice density

The bin-level underutilization revealed by the experiment is not accidental.

Operators are not failing to use the system correctly. They are actively compensating for architectural constraints.

In practice, this often includes:

Leaving bins intentionally underfilled to avoid rehandling penalties

Spreading SKUs across storage bins to reduce digging, waiting time, and workstation dwell — in order to complete orders within SLA

Duplicating inventory to protect service levels

Introducing additional slack to absorb volatility

Explicitly trading space efficiency for predictability

What appears as wasted air is often deliberate operational insurance. The system rewards stability — so operators create it, even when doing so quietly erodes effective density.

The unavoidable implication for “best-in-class density”

Once bin-level utilization is measured empirically, the density claim can no longer be absolute.

The correct statement is no longer:

“AutoStore is the most space-dense ASRS.”

It becomes:

“AutoStore can be highly space-dense under specific operating assumptions.”

That distinction is irreversible once real-world data exists.

Where cube systems can still make sense

None of this invalidates cube-based ASRS.

They remain highly effective for:

Medium- to slow-moving SKUs

Long-tail inventory

Store replenishment

Applications with relaxed or predictable delivery SLAs

They become increasingly strained when forced to operate as ultra-responsive, high-volatility, consumer-facing fulfillment engines — a role they were never originally designed to serve.

The real question buyers — and operators — should now ask

For many past, current, and future buyers, the ASRS selection process begins with a widely held assumption:

Most tier-one ASRS vendors deliver broadly comparable productivity.

Throughput, pick rates, and labor efficiency are often viewed as roughly equivalent once systems are properly sized and engineered. As a result, final purchasing decisions frequently pivot to a different differentiator.

Space efficiency.

In that comparison, cube-based systems — most notably AutoStore — are almost universally positioned, promoted, and ultimately selected as the clear winner. They are widely perceived as the most space-efficient option among all ASRS technologies, and this perception alone has driven a large number of multi-million-dollar buying decisions.

The underlying logic appears sound:

If productivity is similar across systems, then the most space-dense solution must be the best long-term choice.

But this is precisely where risk enters the decision.

Because when that density advantage is assumed rather than measured — and when internal utilization cannot be clearly observed, measured, or actively managed — the foundational premise of the investment is never fully validated.

For customers making a career-defining, multi-million-dollar ASRS decision, discovering after go-live that storage density must be deliberately relaxed — bins underfilled, SKUs spread, inventory duplicated — simply to achieve the required speed, throughput, or service levels can be deeply disappointing.

Not because the system failed. But because the original decision was anchored to a density promise that could not be sustained under real operating conditions.

Which leads to a more important question than buyers have traditionally asked.

The question is no longer:

How dense is my grid?

It is:

Do I have clear visibility into how effectively my storage volume is actually being used — bin by bin, over time — especially as operational pressure increases?

Because empty space is expensive.

And low workstation productivity erodes expected ROI and directly impacts customer delivery performance.

Empty space that remains invisible during planning, expansion, and scaling decisions inevitably leads to poor outcomes — particularly premature grid expansions, unnecessary capital deployment, and long-term system oversizing.

This experiment does not merely challenge a marketing claim.

It exposes a blind spot that has quietly shaped ASRS purchasing decisions for years — and makes the cost of that blind spot visible for the first time.