Is Your AutoStore Ready For Its Nike Tracksuit Moment?

How One Black Swan Event Ends the ASRS Speed Debate

If you are evaluating purchasing an automated storage and retrieval system (ASRS) today, you are almost certainly evaluating a cube system. In practice, that means evaluating some variation of an AutoStore-style architecture. Cube-based systems now represent the dominant share of deployed ASRS capacity, and they have become the default answer in many automation conversations.

That matters, because when one architectural approach becomes the standard, its strengths — and its weaknesses — stop being vendor-specific. They become systemic.

This blog is not about density. That debate is settled.

It is not about robot counts or ports or tuning.

It is about speed — and how one small black swan event is enough to quietly dismantle how speed is usually understood in cube-based ASRS.

Speed, as it is usually measured, is conditional

ASRS speed is almost always presented in steady-state terms:

picks per hour, average cycle time, robots per grid, ports per system.

These numbers are not imaginary. They are simply conditional.

They assume that the right inventory is already reasonably accessible — that physical position and relevance are aligned. When that assumption holds, cube systems can look extremely fast.

The problem is that modern demand no longer respects that assumption.

Digging is not a flaw — it is the mechanism

Digging is not an edge case in cube systems.

It is not a tuning issue.

It is not something that can be engineered away.

It is how access is achieved.

A bin is rarely directly accessible. Retrieving one bin requires moving others out of the way. Sometimes shallow. Sometimes deep. Always present.

You can add robots.

You can add ports.

You can expand the grid.

Digging still exists, because digging is the price paid for compaction.

Under stable demand, digging behaves statistically. Frequently accessed bins tend to migrate upward over time. The system self-corrects — eventually.

That word, eventually, does most of the work.

The black swan that matters is not volume

The industry prepares extensively for volume shocks: peak days, holidays, promotions. These are known stresses. They are modeled, staffed, and budgeted.

The black swan that breaks the speed narrative is not volume.

It is relevance inversion.

One SKU, historically slow, correctly buried, irrelevant for years — suddenly becomes critical. Not gradually. Instantly. And not at one site, but everywhere.

That is the event cube systems are structurally slow to absorb.

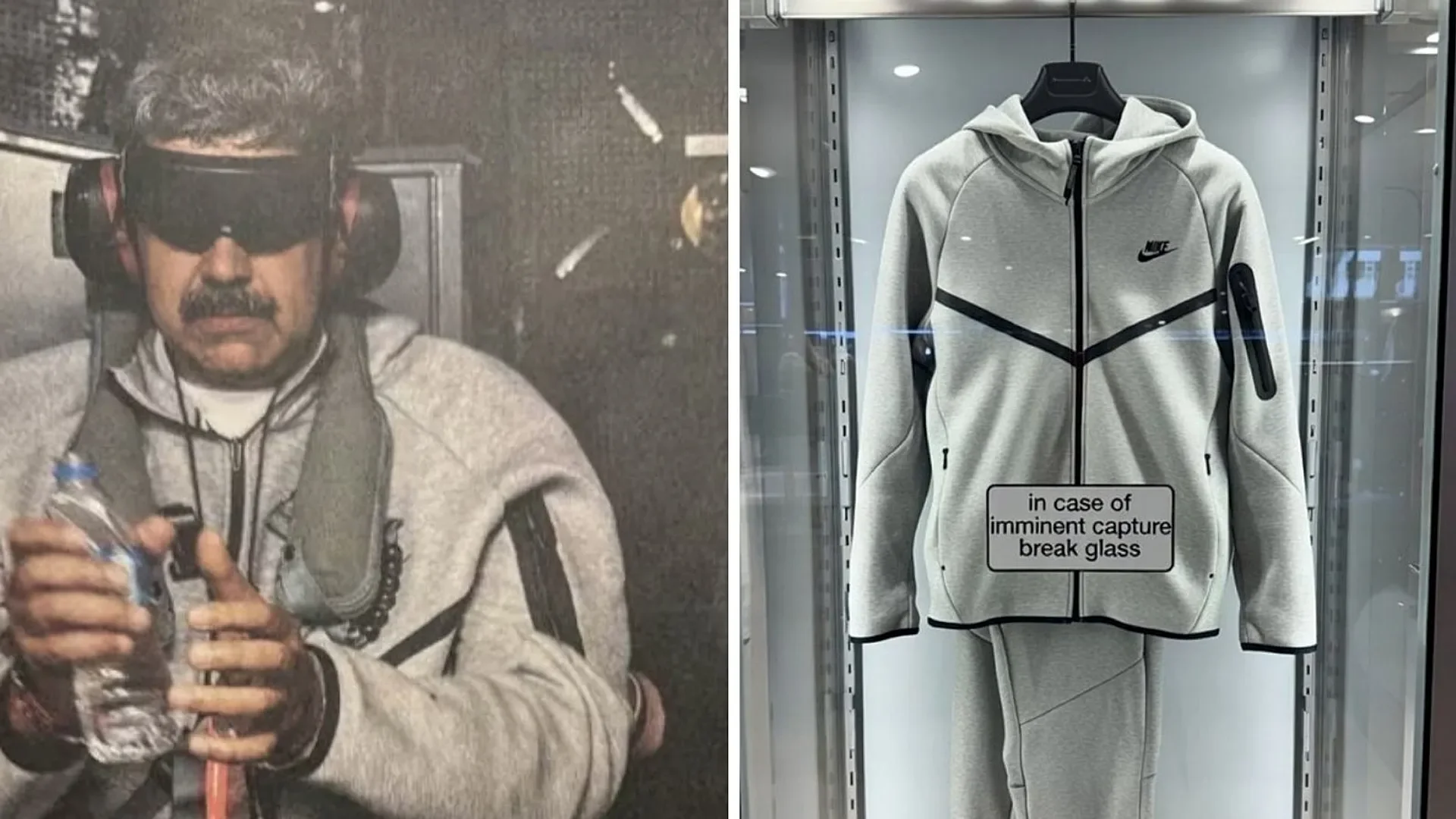

The Madero Nike tracksuit moment

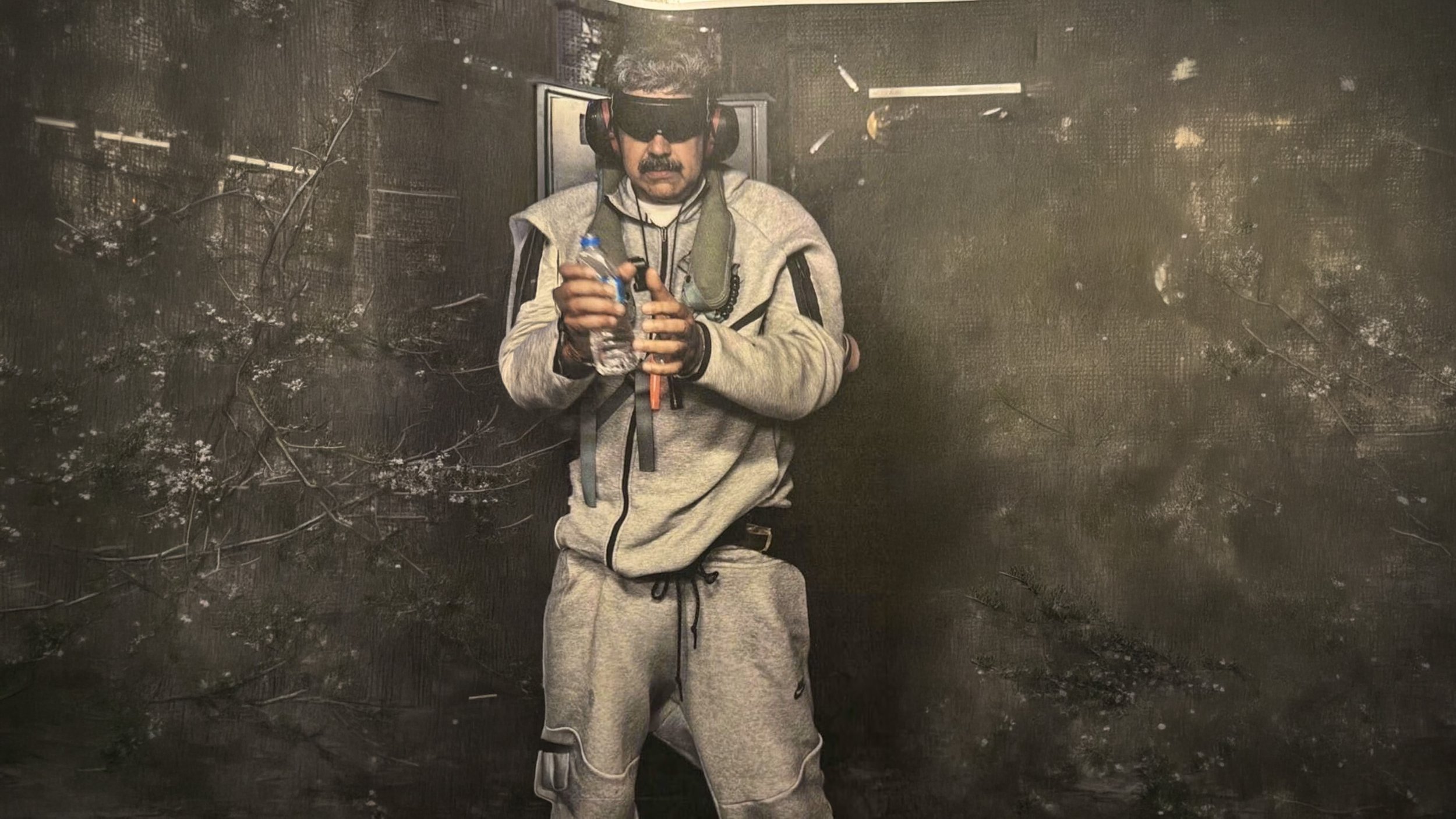

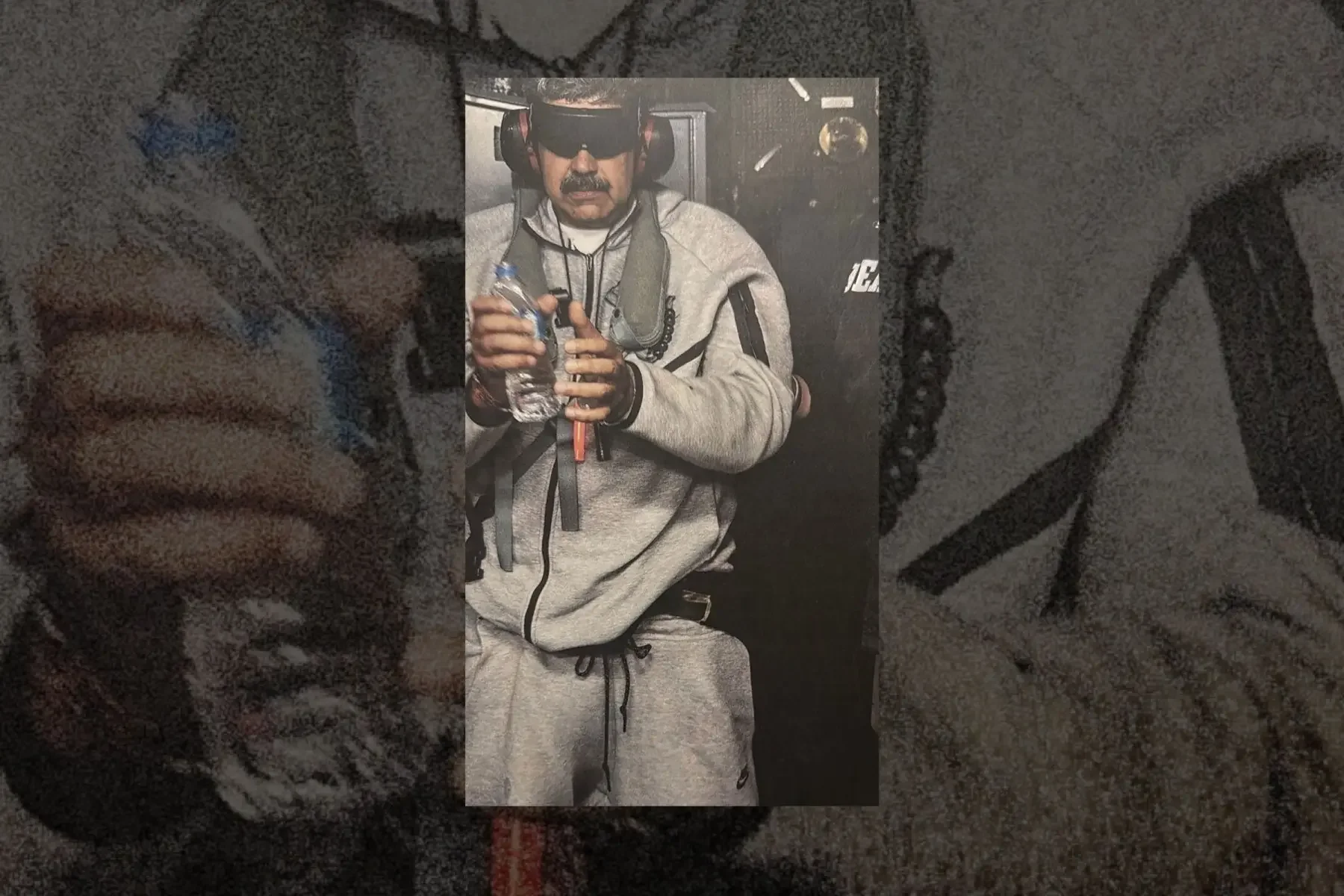

Earlier this year, photographs circulated showing Nicolás Maduro being taken into U.S. custody wearing a grey Nike tracksuit. The image moved instantly across global media and social platforms. What drew attention was not politics, but familiarity. A globally recognizable logo reframed the moment before political meaning had time to settle.

Searches for the tracksuit spiked. The product sold out across multiple channels. There was no campaign, no announcement, no attempt by the brand to insert itself into the moment.

Demand did not emerge because the product changed.

It emerged because attention did.

Social media responses were telling. Many users remarked that they had owned the same tracksuit for years. Others joked that the collection was older than Maduro’s moustache.

That detail matters.

It tells you exactly where that SKU would live in a cube-based ASRS.

A product that old, that quiet, that unremarkable would have been naturally slotted deep — gathering dust at the bottom of the grid. Not because of an error, but because the system did exactly what it was designed to do. History said it didn’t matter. So the system buried it.

Then relevance flipped.

When relevance flips faster than the grid can move

Natural slotting only works after access events occur. But the first access events are already expensive.

Every retrieval requires deeper digging than usual.

Every retrieval interferes with others.

Congestion increases.

Queues form.

Ports starve.

Here is the inversion that quietly kills the speed narrative:

The more popular the SKU becomes, the worse the system performs.

That is not a software bug. It is geometry.

The system is behaving correctly — just under conditions it was never meant to adapt to quickly.

Why nothing appears broken

This is what makes these events operationally dangerous.

Robots keep moving.

Inventory remains accurate.

Dashboards stay mostly green.

But latency creeps in everywhere. Wait times stretch. Variance explodes. Throughput targets are missed without a clear failure point.

From the outside, the system looks busy.

From the inside, it feels slow.

Operators respond rationally to the signals they see: more robots, more ports, more shifts. All of which increase motion — and none of which remove digging.

Speed does not return. It is normalized away.

Normalization is the real risk

The risk in the Nike tracksuit moment was not that branding overtook politics, but that it altered how consequence was felt. A moment that should have registered as destabilizing was rendered familiar, legible, and easily consumed.

Power was not diminished. It was normalized.

Cube systems behave the same way.

Digging does not cause a spectacular failure. It diffuses delay into something operationally manageable. Latency becomes familiar. Variance becomes routine. Performance degradation becomes ordinary.

And once delay feels ordinary, it stops being questioned.

Why this is no longer rare

A decade ago, these relevance inversions were uncommon. Today, they are routine.

Social platforms synchronize attention globally. Online retail collapses geography. Products do not ramp into importance — they flip.

One SKU can go from irrelevant to dominant in hours, across hundreds of independent ASRS sites at the same time.

When cube systems represent the majority of deployed ASRS capacity, this failure mode stops being theoretical. It becomes systemic.

@cbsmornings A surprising fashion moment followed the arrest of Nicolás Maduro, after photos showed him wearing a Nike Tech tracksuit, sending searches for the outfit soaring and helping versions of it sell out online and resell for hundreds of dollars. #nicolasmaduro #nike #tracksuit #outfit ♬ original sound - CBS Mornings

The speed debate quietly ends here

At this point, arguing about the “fastest ASRS” becomes a category mistake.

Fast at what?

Steady state?

Average conditions?

After the system has had time to correct itself?

None of those matter when relevance changes faster than physical reordering.

Speed that depends on history remaining valid is not speed under modern commerce. It is conditional performance.

What buyers need to internalize

This is not an argument against cube systems.

It is an argument for understanding them honestly.

Buying a cube-based ASRS also means buying:

digging cost

adaptation delay

performance variance under shock

Those costs do not appear on spec sheets. They appear when one SKU surprises you.

Black swan events are no longer rare. They are part of how demand works now.

If your system only becomes fast again after it hurts, that pain is not a failure. It is the price of the architecture.

Final thought

Cube systems are extraordinarily efficient at storing uncertainty.

They are far less efficient at responding when uncertainty becomes urgent.

Digging does not make them slow.

It makes their speed conditional.

And one black swan is all it takes to discover what those conditions really are.

The AutoStore Density Claim Meets Measured Reality

For years, cube-based ASRS systems — most notably AutoStore — have been positioned as the most space-dense storage solutions available. The claim has been repeated so consistently that it is now widely accepted as fait accompli, even by competitors across the industry.

Until recently, however, no one had the empirical data required to meaningfully challenge that assumption.

That has now changed.

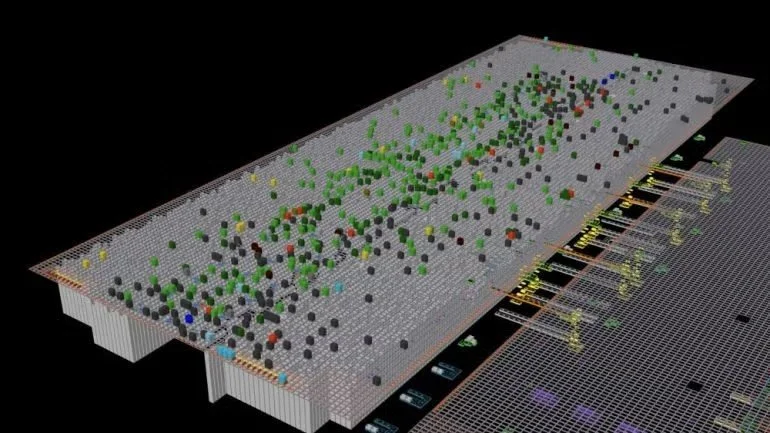

A third-party robotics company conducted a comprehensive, empirical study on a live AutoStore installation, using direct visual inspection to measure how storage volume was actually being utilized. This was not a simulation. Not a benchmark. Not inferred WMS or configuration data.

It was direct observation of physical reality.

Approximately 66,000 bin images were analyzed from a live production system. The results are statistically robust, internally consistent, and — within the automation industry — extraordinarily rare in their level of accuracy.

The findings are unequivocal:

85.8% of total bin volume was empty

More than 93% of bins were filled less than 25%

Only a negligible fraction of bins approached high utilization

These numbers are not debatable. They are not opinions.

They are measurements of what is physically inside the bins.

At this point, the discussion about storage density can no longer remain theoretical.

Why this experiment cannot be dismissed

In warehouse automation, most performance claims rest on assumptions: simulations, design models, or idealized operating conditions. This experiment avoids every common mechanism vendors typically rely on to deflect scrutiny.

It cannot be disclaimed by AutoStore, nor by its global dealer network, for straightforward reasons:

The data comes from a live production system

It is based on direct visual evidence, not inferred metrics

The sample size is large enough to eliminate statistical anomalies

The methodology measures physical reality, not configuration intent

The results are internally consistent across tens of thousands of bins

There is no credible counterargument to what the bins actually contain.

Disagreement remains possible — but only at the level of interpretation, not fact.

What this data forces us to confront

The immediate conclusion is not that AutoStore is “inefficient.”

That would be both inaccurate and intellectually lazy.

The real conclusion is more uncomfortable:

Theoretical density and effective density are no longer the same thing.

Cube systems may still be structurally dense by design. But under modern operating conditions, their realized density can diverge dramatically from their design promise — and the system itself provides no native mechanism to see or continuously measure that divergence.

A system designed for the 1990s, operating in the 2020s

Cube-based ASRS architectures were conceived in an era characterized by:

Stable SKU catalogs

Predictable demand patterns

Batch-oriented fulfillment

Store replenishment and wholesale flows

Delivery SLAs measured in days

That design context matters.

Today’s commerce environment looks very different:

Exploding SKU counts and long-tail assortments

Social- and influencer-driven demand spikes

Continuous order release

Same-day and next-day delivery expectations

Constant re-prioritization and re-slotting pressure

The system did not become worse. The operating assumptions changed.

Why AutoStore operators may intentionally sacrifice density

The bin-level underutilization revealed by the experiment is not accidental.

Operators are not failing to use the system correctly. They are actively compensating for architectural constraints.

In practice, this often includes:

Leaving bins intentionally underfilled to avoid rehandling penalties

Spreading SKUs across storage bins to reduce digging, waiting time, and workstation dwell — in order to complete orders within SLA

Duplicating inventory to protect service levels

Introducing additional slack to absorb volatility

Explicitly trading space efficiency for predictability

What appears as wasted air is often deliberate operational insurance. The system rewards stability — so operators create it, even when doing so quietly erodes effective density.

The unavoidable implication for “best-in-class density”

Once bin-level utilization is measured empirically, the density claim can no longer be absolute.

The correct statement is no longer:

“AutoStore is the most space-dense ASRS.”

It becomes:

“AutoStore can be highly space-dense under specific operating assumptions.”

That distinction is irreversible once real-world data exists.

Where cube systems can still make sense

None of this invalidates cube-based ASRS.

They remain highly effective for:

Medium- to slow-moving SKUs

Long-tail inventory

Store replenishment

Applications with relaxed or predictable delivery SLAs

They become increasingly strained when forced to operate as ultra-responsive, high-volatility, consumer-facing fulfillment engines — a role they were never originally designed to serve.

The real question buyers — and operators — should now ask

For many past, current, and future buyers, the ASRS selection process begins with a widely held assumption:

Most tier-one ASRS vendors deliver broadly comparable productivity.

Throughput, pick rates, and labor efficiency are often viewed as roughly equivalent once systems are properly sized and engineered. As a result, final purchasing decisions frequently pivot to a different differentiator.

Space efficiency.

In that comparison, cube-based systems — most notably AutoStore — are almost universally positioned, promoted, and ultimately selected as the clear winner. They are widely perceived as the most space-efficient option among all ASRS technologies, and this perception alone has driven a large number of multi-million-dollar buying decisions.

The underlying logic appears sound:

If productivity is similar across systems, then the most space-dense solution must be the best long-term choice.

But this is precisely where risk enters the decision.

Because when that density advantage is assumed rather than measured — and when internal utilization cannot be clearly observed, measured, or actively managed — the foundational premise of the investment is never fully validated.

For customers making a career-defining, multi-million-dollar ASRS decision, discovering after go-live that storage density must be deliberately relaxed — bins underfilled, SKUs spread, inventory duplicated — simply to achieve the required speed, throughput, or service levels can be deeply disappointing.

Not because the system failed. But because the original decision was anchored to a density promise that could not be sustained under real operating conditions.

Which leads to a more important question than buyers have traditionally asked.

The question is no longer:

How dense is my grid?

It is:

Do I have clear visibility into how effectively my storage volume is actually being used — bin by bin, over time — especially as operational pressure increases?

Because empty space is expensive.

And low workstation productivity erodes expected ROI and directly impacts customer delivery performance.

Empty space that remains invisible during planning, expansion, and scaling decisions inevitably leads to poor outcomes — particularly premature grid expansions, unnecessary capital deployment, and long-term system oversizing.

This experiment does not merely challenge a marketing claim.

It exposes a blind spot that has quietly shaped ASRS purchasing decisions for years — and makes the cost of that blind spot visible for the first time.