Will Ocado Be the Next Attabotics?

It’s a provocative question — but no longer an unreasonable one.

Ocado is facing reports of up to 1,000 job cuts, renewed cost-cutting pressure, multiple customer warehouse closures in North America, and an explicit mandate to reach cash-flow positivity in 2025/26.

If that combination sounds familiar, it should.

Attabotics followed a similar arc: ambitious technology claims, heavy R&D spending, aggressive growth narratives — followed by market reality, customer friction, cash pressure, and ultimately a reset that came too late.

Ocado is not Attabotics.

But the risk pattern is starting to rhyme.

Automation and robotics are brutally difficult businesses. Attabotics never truly internalized that reality, and its response to the Canadian Tire fire effectively marked the end of its automation journey.

The uncomfortable question is whether Sobeys’ failure in Calgary will eventually play the same role for Ocado.

It is also worth stating the obvious: Ocado is not a startup. Founded in 2000, it is now a 26-year-old company, not a young venture discovering hard truths for the first time.

The Warning Signs Are No Longer Subtle

Recent reporting suggests Ocado plans to eliminate roughly 5% of its global workforce, with cuts concentrated in UK head-office technology and back-office functions.

That matters — because it signals a shift away from heavy platform development toward cost containment and operational efficiency.

Ocado’s own leadership has acknowledged it is at the “tail end” of its major technology build-out phase.

Translation:

The era of unlimited R&D spending is over. Execution and commercial scalability now have to carry the business.

This is where many automation companies stumble.

The North American Reality Check

Ocado’s biggest challenge is not revenue growth — it is deployment outcomes.

Sobeys closed its Calgary robotic CFC

Kroger shut down three Ocado-run automated warehouses

A planned Kroger site in Charlotte was cancelled

Several deployments have been “re-scoped” rather than expanded

These are not edge cases. These are Tier-1 customers making hard decisions based on real operating data.

When marquee partners pause, downsize, or exit, uncomfortable questions follow:

Is the solution over-engineered?

Is the cost structure misaligned with demand?

Is throughput flexible when volumes soften?

Does the model still work without e-grocery hypergrowth?

Attabotics faced the same questions — and never recovered once customer confidence eroded.

Revenue Growth vs. Cash Reality

On paper, Ocado’s numbers look respectable:

Group revenue up double digits

Technology solutions revenue growing faster than retail

A global customer list across Japan, Korea, and Australia

And yet:

Pre-tax losses remain near £375M

Shares are down over 70% in five years

The company has publicly committed to cost discipline over expansion

This divergence — growing technology revenue alongside shrinking ambition — is exactly where automation narratives tend to break down.

Selling automation is one thing.

Operating it profitably, repeatedly, and predictably is another.

Will the Upcoming MODEX Announcement Save Ocado?

In parallel with these pressures, Ocado is preparing a major announcement at MODEX.

The messaging will almost certainly emphasize familiar themes:

Software evolution

Modularity

Greater flexibility

Faster deployment narratives

Broader market access following expired exclusivity

All of this sounds directionally correct.

But the real question is not what Ocado announces at MODEX.

The real question is whether a MODEX announcement, at this stage, can materially change the company’s trajectory.

Trade-show announcements do not change physics.

They do not fix deployment economics.

They do not reverse customer closures.

And they do not restore confidence once Tier-1 operators start pulling back.

Attabotics also had confident announcements, polished messaging, and compelling narratives — right up until the economics stopped working.

At this point, MODEX is less a launchpad and more a stress test.

Additional Friction Ocado Rarely Addresses

Beyond the headline financial and deployment issues, Ocado faces several structural and cultural challenges that are rarely discussed openly:

Ocado cannot compete head-on with AutoStore’s global marketing and partner ecosystem

The company has done very little to meaningfully engage with the broader automation community

Its culture often comes across as insular and arrogant, rather than collaborative

Ocado facilities are rarely opened to the public or third-party observers

The company has a reputation for lawyering up quickly rather than engaging transparently

Ocado has never clearly demonstrated how its on-grid robotic picking is superior to a well-designed goods-to-person workstation

Its software and hardware stack is 100% proprietary and black-box, creating a fully vendor-locked system

This runs directly counter to what increasingly sophisticated end users are asking for: interoperability, orchestration independence, and exit optionality

Meanwhile, there is a global shift toward store-based fulfillment, with retailers increasingly picking online orders directly from their physical stores rather than betting exclusively on centralized automated warehouses

These factors matter — because automation success is no longer just about technology.

It is about trust, openness, economics, and optionality.

The Core Risk: Automation Built for Yesterday’s Assumptions

Both Ocado and Attabotics share a structural vulnerability.

They were designed for a world of rapid e-grocery growth, stable labor substitution economics, and predictable order profiles.

That world has changed.

Today’s operators want:

Incremental automation

Phased deployment

Software-led orchestration

Mixed manual + automated workflows

Clear exit paths if demand shifts

Big, centralized, monolithic automated warehouses are no longer a default “safe bet.”

So… Will Ocado Be the Next Attabotics?

Not necessarily.

Ocado still has:

Strong engineering talent

Real deployments in production

A global customer footprint

Time — if it uses it wisely

But the risk window is open.

If Ocado:

Over-indexes on marketing narratives

Under-addresses deployment economics

Cuts too deeply into core technical competence

Fails to align automation scale with real demand volatility

Then the comparison will stop being hypothetical.

What This Means for Retailers

The more important question is not whether Ocado survives.

It is this: Should retailers still be betting their future on single-vendor, highly centralized automation platforms?

The industry’s recent history — Attabotics included — suggests that caution is no longer optional.

Sobeys Pulls the Plug on Ocado’s Robotic Cube Warehouse

Ocado’s Reset: Another Robot-Heavy Fulfillment Center Shuts Down

Another automated fulfillment center.

Another “strategic reset.”

Another reminder that scale, robotics, and software do not magically create demand — or profitability.

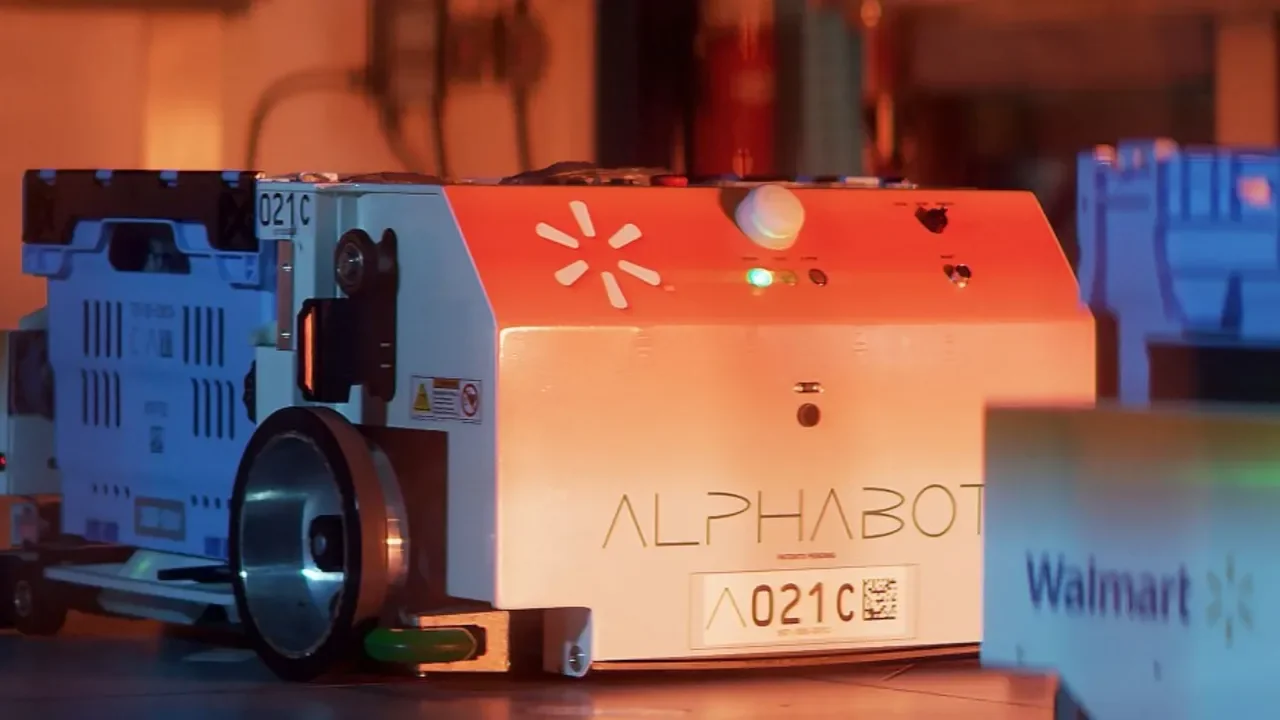

This week, Ocado Group confirmed that its Canadian partner Sobeys will close the Calgary robotic customer fulfillment centre (CFC) using Ocado’s automation technology. The market reaction was swift: Ocado’s shares fell nearly 10%.

This follows closely on the heels of Kroger shutting down three Ocado-powered CFCs in the U.S. less than three months ago.

Different geographies.

Different partners.

Same outcome.

Sobeys to launch automated Ocado online fulfillment center in Vancouver

The Explanation Is Familiar — and Incomplete

Sobeys cited “market size” and “slower-than-expected e-commerce growth in Alberta.” That may be true. But it avoids the harder question:

Why do these highly automated, capital-intensive facilities require everything to go perfectly just to break even?

Large robot-run fulfillment centers are structurally brittle:

They demand high, sustained order density

They lock retailers into fixed cost curves

They struggle with regional demand variability

And they leave little room for graceful scaling down

When growth underperforms — even slightly — the economics collapse.

Centralized Automation vs. Flexible Fulfillment

Ocado’s model was built for a very specific future:

high online grocery penetration, predictable volumes, and centralized demand.

North America didn’t cooperate.

Instead, retailers are increasingly leaning toward:

Store-based picking

Micro-fulfillment

Hybrid networks

Faster, cheaper last-mile models

Not because they’re “less automated” — but because they’re more adaptable.

As the article notes, competitors using store-based fulfillment and local delivery (bikes, mopeds, short hops) are often cheaper, faster, and easier to adjust than massive robot-only CFCs.

Losses, Resets, and “Evolved Technology”

Ocado will receive £18m in compensation, but lose £7m in annual fee revenue. Revenue is up — yet losses persist.

This has become a familiar pattern:

Expensive deployments

Slow ramp-ups

Network “refinements”

Strategic resets

New versions of the technology promised to fix the last one

Ocado now says its North American business is being “reset” and points to its newer Swift Router system. Maybe it helps. But software improvements cannot fully offset a mismatched operating model.

The Bigger Takeaway

Some analysts are now openly questioning whether large, robot-centric fulfillment centers can work economically in developed markets like the U.S. and Canada.

That debate is overdue.

This isn’t an indictment of robotics.

It’s an indictment of rigid automation strategies that assume volume will eventually save the model.

It won’t.

Flexibility beats density.

Adaptability beats elegance.

And software orchestration matters more than robot count.