Ocado Expands Cube Automation Beyond Grocery

Ocado has delivered a cube-based automation system for McKesson Canada, representing a continued expansion of its technology beyond e-commerce grocery fulfilment.

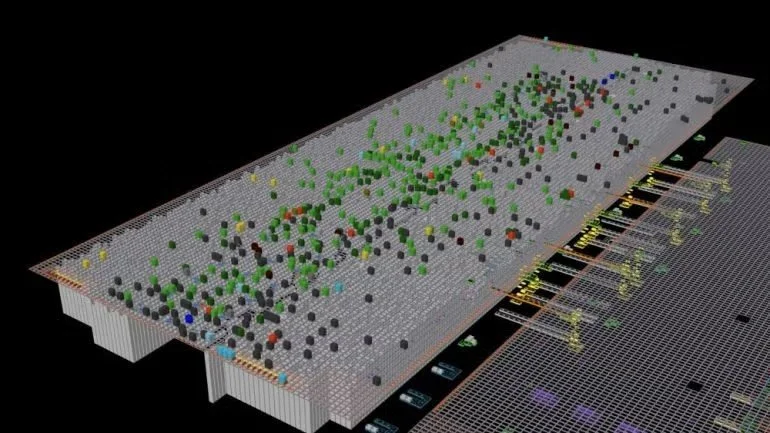

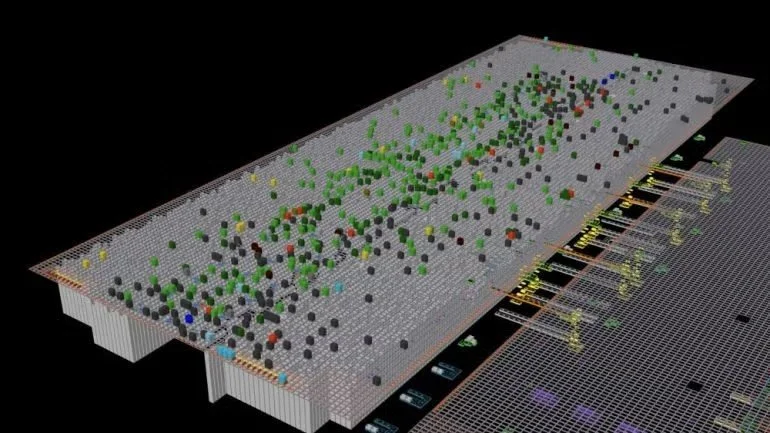

The installation includes approximately 230,000 storage locations and more than 575 robots, making it one of the largest cube-based systems worldwide — including among large AutoStore deployments. It is firmly within enterprise-scale deployment territory, not a pilot or limited-scope implementation.

The project is strategically important for Ocado at a time when cube-based automation is being actively debated across the industry. Questions around scalability, vertical applicability, and long-term operational behaviour are increasingly discussed at senior supply chain and engineering levels, particularly as organizations evaluate cube architectures alongside shuttle, mini-load, and hybrid ASRS alternatives.

In that context, the McKesson deployment provides Ocado with a significant reference point demonstrating that its cube-based approach can be applied beyond food and online grocery fulfilment. The project effectively serves as a showcase that the architecture can be transferred across industries, operational models, and workflow requirements — an important signal for organizations exploring cube automation outside traditional retail environments.

Equally notable is how the project has been structured. Unlike Ocado’s grocery partnerships — which were built around multi-site strategic alliances and platform-style commercial arrangements — the McKesson deployment follows a more conventional automation model, with milestone payments during construction, final acceptance upon installation, and ongoing service and maintenance fees. This aligns closely with standard industrial automation procurement practices.

From an operational standpoint, pharmaceutical distribution introduces a different set of priorities. High accuracy requirements, controlled inventory handling, and sensitivity to workflow stability place greater emphasis on exception management, replenishment behaviour, and the interaction between automated storage and surrounding processes.

The deployment also reinforces that cube automation cannot be treated as a single interchangeable category. While Ocado and AutoStore are frequently grouped together due to their shared cube geometry, the operational behaviour of the two architectures differs in meaningful ways. Throughput scaling strategy, robot interaction density, buffering mechanics, and integration philosophy all influence how each system performs under sustained production conditions. As deployments move beyond retail fulfilment and into more workflow-sensitive environments, these differences become increasingly relevant, particularly when evaluating responsiveness to workload variability, system recovery behaviour, and the role of the surrounding orchestration layer.

As cube automation continues expanding across verticals, the discussion is shifting away from simple applicability and toward how different implementations behave under real operational conditions — and how effectively they integrate with the broader warehouse workflow.