Humanoid Robots in Warehouses: Productivity, Perception, and Operational Reality

Recent commentary from one of China’s leading humanoid robot manufacturers offers a useful reality check for the logistics and warehouse automation industry.

UBTech, a Shenzhen-based humanoid robotics company with partnerships including BYD and Foxconn, has publicly acknowledged that its latest humanoid robots currently achieve only 30–50% of human productivity, and only in tightly constrained tasks such as box stacking and basic quality inspection.

While this admission has drawn attention in manufacturing circles, its implications are particularly important for warehousing and logistics operations, where productivity, throughput, and reliability are unforgiving metrics.

Warehouses Don’t Pay for “Human-Like” — They Pay for Throughput

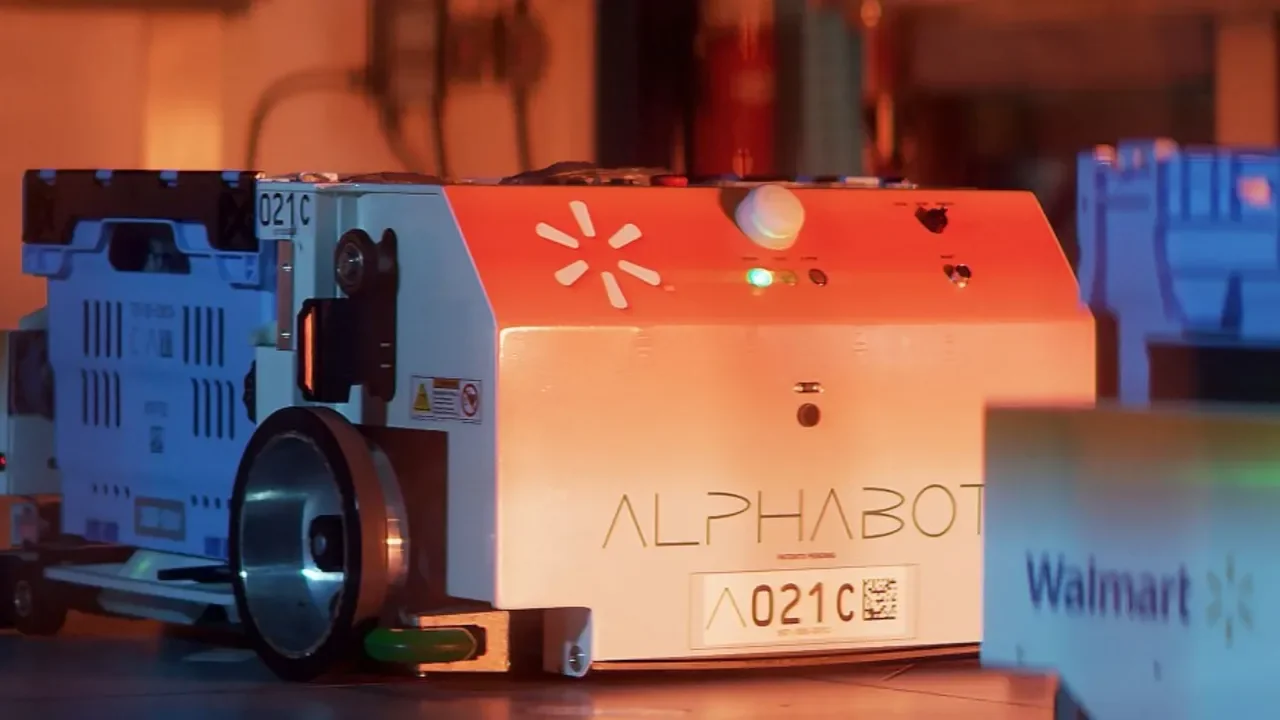

Warehouse automation has never been about building machines that resemble humans. It has been about moving cartons, totes, pallets, and SKUs as efficiently, predictably, and economically as possible.

In this context, a humanoid robot operating at half the productivity of a human picker raises immediate questions:

How does this compare to AMRs, conveyors, sorters, or shuttle systems?

What is the effective cost per pick, per move, or per hour?

How many humanoids would be required to match the throughput of one task-optimized system?

For most warehouse workflows—case picking, palletizing, replenishment, goods-to-person, cross-docking—the answer is uncomfortable: humanoid robots are competing against systems that already outperform humans by a wide margin, not merely match them.

Flexibility Sounds Attractive — Until You Model It

Proponents of humanoid robots often argue that their ability to operate in “human-designed” environments makes them ideal for brownfield warehouses. In theory, this flexibility avoids major infrastructure changes.

In practice, warehouses are not neutral environments.

They involve:

Various aisles

Congested intersections

Variable floor conditions

Tight cycle-time constraints

Safety separation between humans and machines

A humanoid robot must balance dynamically, carry its own power supply, coordinate dozens of actuators, and make real-time decisions in environments that are far more chaotic than factory demos suggest.

Each of these challenges adds variability—something warehouse operations work relentlessly to eliminate.

The Hidden Cost: Reliability, Not Intelligence

In logistics, downtime matters more than intelligence.

A robot that is theoretically versatile but operationally fragile introduces risk:

Battery limitations

Mechanical wear across many joints

Recovery complexity when faults occur

Slower mean time to repair compared to simpler systems

Even UBTech has acknowledged that its current humanoids require manual intervention to switch end effectors for different tasks—undercutting the idea of seamless general-purpose labor.

This is not a software problem alone. It is a physics, maintenance, and systems-engineering problem.

Proof-of-Concept Is Not Throughput

Many humanoid robot deployments today remain at proof-of-concept or demonstration stage, often in controlled or government-supported environments.

That matters.

Warehouse automation systems are not evaluated on whether they can perform a task once—but whether they can do it:

20 hours a day

Across seasonal peaks

With predictable performance

At scale

Analysts have correctly noted that most humanoid deployments tell us little about commercial viability in live warehouse operations. A robot carrying a box in a demo video is not the same as sustaining thousands of picks per hour across multiple zones.

80% Human Productivity Is Not the Benchmark Warehouses Use

UBTech has stated a goal of reaching 80% of human productivity by 2027, with the argument that robots do not need breaks or holidays.

But this framing misses how warehouses actually make automation decisions.

The benchmark is not human productivity.

The benchmark is system productivity per dollar invested.

In most logistics environments:

Conveyors don’t get tired

Sorters don’t call in sick

ASRS systems don’t suddenly need to be reset

AMRs don’t replicate human joints because they don’t need to

Humanoid robots are not competing against people—they are competing against decades of highly optimized material-handling systems.

Where Humanoids Might Make Sense

There are limited scenarios where humanoid robots could eventually find a role in logistics:

PR or marketing goals to use in companies’ social media.

Highly constrained brownfield sites with no automation infrastructure

Low-throughput, high-variability tasks

Environments where retrofitting is prohibitively expensive

Even in these cases, success will depend less on humanoid form factors and more on integration, orchestration software, and reliability engineering.

The Bigger Question Warehouses Should Be Asking

The real question is not whether humanoid robots will improve—they will.

The question is whether humanoid form factors are the right abstraction for warehouse work at all.

Warehousing is about flow, not resemblance.

About predictability, not novelty.

About systems, not individual machines.

Until humanoid robots can demonstrate sustained, measurable advantages over task-optimized automation in live warehouse environments, they remain an interesting technology—not yet an operational answer.